The most powerful names in my world aren’t coaches like Krzyzewski, Calipari, or Self; or institutions like Duke, Kentucky or Kansas; or even “non-profits” like the ACC, SEC or Big 12; or even the NCAA itself. If you want to know who has the power, ignore the millionaire coaches. Don’t bother following the ten-figure TV rights deals. You’ll find some of it in the venerable hoops palaces with names like Rupp Arena, the Dean Dome or Allen Fieldhouse, but that’s not where it starts.

No, if you’re trying to find out who really has the juice, the real power, you’d do better to show up at venues like the LakePoint sporting complex in Atlanta, the Riverview Park Activities Center in North Augusta, the Hoover Metropolitan Complex in Birmingham or the Boo Williams Sportsplex in Hampton. Follow the signs that say EYBL, adidas Gauntlet or The Under Armour Association.

If this is starting to sound like an underground fight club, don’t worry. It’s all out there for the public to see. But much like the fictional Fight Club, the first rule is that nobody talks about what’s really going on. So when you show up at one of these venues on a weekend in April, May or July, find a seat or stand along the wall, close your eyes and listen. You hear that? Those quick, high-pitched squeaks are something like the unofficial soundtrack of basketball. The friction of rubber soles against a hardwood floor. It’s a beautiful thing. There’s a purity to it. That sound happens everywhere the game is played. It’s ubiquitous. You don’t need a scoreboard, or referees, or announcers, or TV crews. All you need is a ball, a basket, and the shoes.

Those shoes, man. Everyone needs them. Everyone.

Now open your eyes and look at every player’s feet, and you’ll see who’s got the juice. It’s symbolized by a check mark, or three stripes, or sometimes by an interlocked U and A. Nike. adidas. Under Armour. A combined market capitalization upward of $160 billion. Yeah, check that number again real quick.

Now look around you. You’ll see the familiar logos of your favorite college athletics programs, probably even your own alma mater, on the polos and jackets of almost everyone there. And among them you’ll see someone who doesn’t appear to be aligned with any particular team, probably dressed head to toe in one particular shoe brand or another.

That’s me. This is my world. The rest of these guys are just passing through. At one point for me it was Nike. At another point it was adidas. In both instances I was a get-it-done guy. Get what done, you may ask?

It.

Whatever it was. As long as it meant that the best teenage basketball players suited up for the youth basketball teams we sponsored, signed to play for the universities we had deals with, and ultimately turned pro, preferably as first-round draft picks going to major-market NBA teams, and did it all while wearing our logo on their shoes, and socks, and shorts, and jerseys, and headbands, and… well, you get the idea.

But long before a Zion Williamson becomes a household name, he’s just a kid, usually a Black kid, and more often than not he’s flat broke. So before he can ever worry about putting a ball in a hoop, he’s gotta survive. Shit, his whole family’s gotta survive. So it was almost with a sense of poetic irony that during Zion’s tremendous one-and-done season at Duke—in which he was named the ACC Player of the Year, a consensus All-American, won both the Naismith and Wooden Awards among a much longer list of remarkable accolades for a mere freshman—the lasting memory of him on the court wasn’t the 28 points he scored in his ballyhooed debut against Kentucky in only 23 minutes of action. Nor was it the 35 he banged on the collective heads of the Syracuse Orangemen. It wasn’t leading the Blue Devils to within two points of the Final Four after a crushing one-point loss to Michigan State in the Elite Eight, or his otherworldly, Bill Russell–esque shot-blocking prowess or the thunderous compilation of dunks that made folks believe that their eyes had the capacity to lie.

No, the moment most remembered came in February 2019. It was the blowout heard around the sports world, when his foot ripped through the Nike, Duke-specific PG 2.5, NBA star Paul George’s signature shoe model as he planted his left foot on the shiny hardwood of Cameron Indoor Stadium against the rival North Carolina Tar Heels in one of the most viewed college basketball games ever aired on ESPN.

Now open your eyes and look at every player’s feet, and you’ll see who’s got the juice. It’s symbolized by a check mark, or three stripes, or sometimes by an interlocked U and A. Nike. Adidas.I say poetic irony because it was a season following what was supposed to be one of the most “explosive” scandals in the history of college hoops. The one I got snagged up in by the FBI. The FBI!!!

But in the same way that Zion returned shortly with no ill effects, continuing his reign atop the game while serving as an unofficial billboard for Nike every time he appeared on television, the college game moved forward with no ill effects, save for the few individuals, myself included, the majority being Black men, middlemen and assistant coaches being cast as some type of rogue organized crime figures who were threatening the so-called sanctity of the game. Which is all utter bullshit.

Michael Sokolove, in the epilogue of his recent book, The Last Temptation of Rick Pitino, when reflecting on Zion’s lone season at Duke, wrote,

To watch Zion play at the end of such a dreary year of college basketball, after all the layers of sleaze that were exposed—after the coaches who talked like gangsters and the self-interested NCAA suits who stayed in duck-and-cover mode—was to be reminded that there is actually some good left in the center of it. It was proof that if you could clear away the corruption, even for a moment, something like pure, joyous competition comes into view.

The statement was absurdly hilarious to me, given that he speaks as if he’s in a pulpit, not knowing what the hell he’s talking about, without the slightest clue as to what went into Zion’s recruitment and the dollars swirling around the young man, a mere pittance of which flowed into his family’s coffers before he cashed in big in the NBA.

Does that make him or his family sleazy gangsters? Of course not. Neither he nor his family created the environment that was designed to exploit them. They were simply playing the game according to the real rules, the Fight Club rules, grabbing what they could off the margins. And, happily, the best-case scenario happened for him. But that is a rarity, and far-fetched from the reality of most poor Black kids that play college basketball.

That phrase Sokolove used, if I’m being honest, still irks me. “After all the layers of sleaze were exposed…” I was obviously lumped into those “layers of sleaze.” At various junctures I was called not only sleaze, but an undesirable and corrupt. These were, among others, the terms used to describe me since the entire ordeal came to light in various media outlets.

It’s typical of those who are so comfortable in their spaces of privilege as it relates to the space of elite college athletics. It’s typical of the uninformed, uneducated and inexperienced, specifically those writers and journalists and other media members pecking away at their computers who are oblivious to how the whole machine operates, casting aspersions about an environment, one in which they cling to the absurd concept of “amateurism” and the facade that allows young Black athletes to be exploited and taken advantage of by the NCAA and universities that falsely claim to have their best interests at heart.

My credibility and reputation were attacked, which was to be expected. My life was upended; my ability to provide for my family was severely compromised. All of this despite the fact I committed no crimes and simply played loosely, as everyone does in this space, from the Rick Pitinos to the Will Wades to the Bill Selfs and countless others, with the Byzantine and exploitative NCAA rules.

Yes, I was in the business of giving the companies that employed me a competitive advantage in the marketplace. But I was also in the business of helping kids and their families. These young men were athletes first and students a very far second. Many were directed toward recreation management majors or other easy, less rigorous courses of study meant to keep them eligible, not educate them. I was dealing with them as people, not property, as well as their families’ real-world issues.

We put groceries in the kitchens of families that didn’t know where their next meal was coming from. We supplied winter coats against bitter winters. We covered doctor and dentist bills out of our own pockets when the situation was dire. Sometimes we personally paid families’ heat, gas or electric bills, so they wouldn’t go without. We ensured mortgage or rent payments got covered, giving athletes and their families a respite from the haunting specter of foreclosure or eviction. So yes, let’s have an honest conversation. Not one based on some fictional fantasy that has Luther Vandross singing “One Shining Moment” in the background right after Baylor has kicked Gonzaga’s ass in the national championship game as the nets are being cut down.

I’m ready to tell my story. And it is my sincere hope that you are ready to listen.

__________________________________

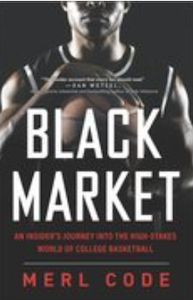

Excerpted from Black Market @ 2022 by Merl Code, used with permission by Hanover Square Press.