Illustrations by Eric Yahnker

I.

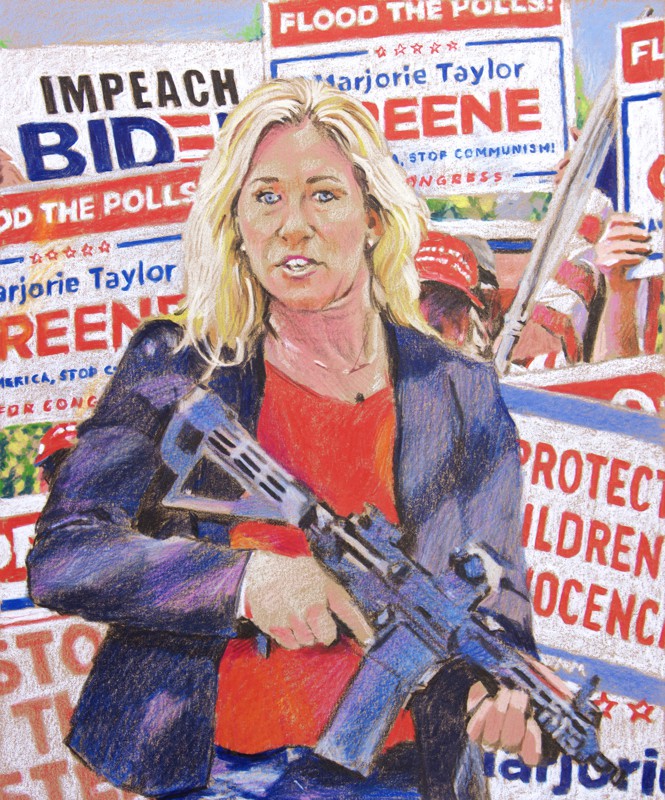

She was very late. A man named Barry was compelled to lead the room in a rendition of Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.” to stall for time. But when she did arrive, the tardiness was forgiven and the Cobb County Republican Party’s November breakfast was made new. She wasn’t greeted. She was beheld, like a religious apparition. Emotions verged on rapture. Later, as she spoke, one man jumped to his feet with such force that his chair fell over. Not far away, two women clung to each other and shrieked. I was knocked to my seat when a tablemate’s corrugated-plastic FLOOD THE POLLS sign collided inadvertently with my head. Upon looking up, I came eye-level with a pistol tucked into the khaki waistband of an elderly man in front of me. “She is just so great,” I heard someone say. “I mean, she really is just amazing.”

Marjorie Taylor Greene arrived in Congress in January 2021, blond and crass and indelibly identified with conspiracy theories involving Jewish space lasers and Democratic pedophiles. She had barely settled into office before being stripped of her committee assignments; she has been called a “cancer” on the Republican Party by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell; and she now has a loud voice in the GOP’s most consequential decisions on Capitol Hill because her party’s leaders know, and she knows they know, that she has become far too popular with their voters to risk upsetting her.

Nobody saw her coming. Not even Greene saw Greene coming.

II.

She was a product, her family loved to say, of the “Great American Dream.” There was a three-story home at the end of a shaded driveway in the small town of Cumming, Georgia, north of Atlanta; there was a finished basement in which Marge—and that is what she was called, Marge—and her friends would gather in faded nylon one-pieces after a swim in Lake Lanier.

[David A. Graham: Marjorie Taylor Greene is just a symptom of what ails the GOP]

Her father was Robert David Taylor, a Michigan transplant for whom a three-story home had never been guaranteed but who had believed acutely in its possibility. Bob Taylor was the son of a steel-mill worker; he had served in Vietnam; he had hung siding to pay for classes at Eastern Michigan University. He had married the beautiful Carrie Fidelle Bacon—“Delle,” to most people, but he called her Carrie—from Milledgeville, Georgia, and rather than continue with college, he had become a contractor and built a successful company called Taylor Construction. For Marjorie Taylor, the first of Bob and Delle’s two children, the result was a world steeped in a distinctly suburban kind of certainty: packed lunches and marble kitchen countertops, semiannual trips to the beach, and the conviction that everything happens for a reason.

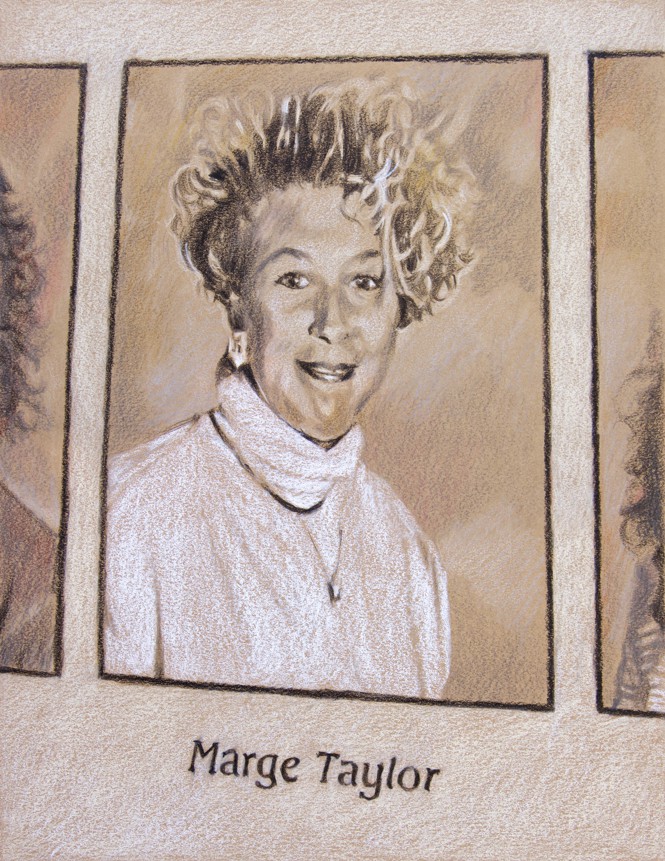

She came of age in Cumming, the seat of Forsyth County. With her turtleneck sweaters and highlighted mall bangs, Marge Taylor might have been any other teenage girl in America. At South Forsyth High School, class of 1992, she was a member of the Spanish club and a manager of the soccer team. She may not have been voted Most Spirited, but she dressed to theme during homecoming week; she may not have had the Best Sense of Humor, but by graduation she had amassed her share of inside jokes with friends. “Shh … It’s the people outside!” her senior quote reads in the high-school yearbook. “Run the cops are here! I’m gone!!” She was “nice to everyone,” “upbeat,” with “tons of confidence,” recalls Leslie Hamburger, a friend of hers and her brother David’s. “I have nothing but good memories.” The good-but-not-great student was hardly, in other words, an overachieving scold already plotting her ascent to Washington. It’s difficult to imagine an 18-year-old Ted Cruz bothering with something called the Hot Tuna Club.

Forsyth County was a calm, quiet, ordered place. But it had a history. In September 1912, an 18-year-old white girl was found bloodied and barely breathing in the woods lining the Chattahoochee River; she died two weeks later. Within 24 hours of her discovery, four Black men had been arrested and charged with assault. A white mob dragged one of the suspects from his cell and hanged him from a telephone pole. Two others were tried and executed. White residents then decided to undertake nothing short of a racial cleansing. On horseback, armed with rifles and dynamite, they drove out virtually all of the county’s Black population—more than 1,000 people. So successful were their efforts that the county would experience the modern civil-rights era vicariously at best. There were no whites only signs to fuss over in Cumming, because there were no Black people to keep separate.

In January 1987, a white resident organized a “Walk for Brotherhood” to commemorate what had happened 75 years earlier. The project was complicated by the immediate wave of death threats he received. Arriving from Atlanta, the civil-rights leader Hosea Williams called Forsyth the most racist county in the South. Oprah Winfrey came down to cover the event. But most people in Forsyth ignored the whole affair; broach it in conversation, and you were considered a pot-stirrer. George Pirkle, the county’s resident historian, was reminded of this as recently as 2011, when he readied for publication The Heritage Book of Forsyth County. He told the mayor of Cumming about his plans to include the region’s Black history in the volume, and got an incredulous response: “Well, why in the world would you want to do that?” As Martha McConnell, the local historical society’s co-president then and now, told me, the subtext was clear: “Don’t be starting things.”

In the end, the Heritage Book did not go starting things. Look through it today and you will see the neatly arranged census data that cuts off at 1910. To include 1920, of course, would have revealed that the Black population was suddenly gone. To go beyond 1920 would have revealed that the Black population never came back.

All of which is to say that Marge Taylor’s worldview was shaped in a community artificially devoid of sociocultural conflict, a history scrubbed of tension. That’s the basic attitude here toward the past, Pirkle told me: “If you don’t talk about it, it goes away.”

Decades later, as they considered her scorched-earth rise to power—the conspiracy theories and racist appeals and talk of violence against Democratic leaders—some of her teachers would find themselves wondering how they’d failed to notice the young Marge Taylor. How was it that they had no memory of her holding forth in civics class, or waging a boisterous campaign for student office? How could it possibly be that in fact they had no memory of her at all?

III.

She did as she was supposed to do, graduating from South Forsyth High and then packing up and moving an hour and a half away, to Athens, for four years at the University of Georgia. She would flit all but anonymously through the campus of 20,000 undergraduates. For Marge Taylor, UGA was about becoming the first in her family to graduate from college—setting herself up to run Taylor Construction. Almost certainly it was also about meeting a nice man. Perry Clarke Greene was a nice man. Three years her senior, he was tall and earnest and came from Riverdale. He, too, was in the university’s Terry College of Business. They exchanged vows the summer before her senior year, in 1995.

Among the things I do not know about Marjorie Taylor Greene—she would not speak with me for this story—is what her wedding was like. A newspaper account, if it exists, has yet to turn up. I do not know whether she stood before an altar laden with white gladioli, as her grandmother once had, or whether the reception was a small affair at her parents’ home in Cumming or something bigger somewhere else. I also do not know whether, on that day, she was happy: whether the quiet and respectable life that now unfurled before the new Mrs. Perry Greene felt like enough.

The young couple moved into a three-bed, three-bath colonial with symmetrical shrubbery in the north-Atlanta suburb of Roswell. Perry Greene became an accountant at Ernst & Young, and Marjorie Greene became pregnant. In January 1998, she smiled alongside the other mothers with tired eyes and loose clothing as they learned to exercise and massage their newborns in the North Fulton Regional Hospital’s “Mother Lore” class.

It wasn’t long before Perry started working for his father-in-law as general manager of the family business. After facilitating the sale of Taylor Construction, in 1999, he moved on to Taylor Commercial, a former division of the company, which specialized in siding for apartment complexes and subsidized-housing projects. Soon after, Bob Taylor named his son-in-law president of the company.

Marjorie, meanwhile, tended to their one, two, and finally three children. There were lake days with Mimi and Papa, three-week Christmas vacations in the sun, and annual drives to visit Perry’s extended family in Oxford, Mississippi. A lot of time was spent traveling to fast-pitch softball tournaments—Taylor, the middle child, was barely a teenager when she started getting noticed. (“Can’t believe she is being recruited in 8th grade,” Greene would write on her personal blog after a weekend at one university.)

As for Taylor Commercial, it was eventually bought by Marge and Perry. Financial-disclosure documents filed in 2020, when Greene first ran for office, reveal a company whose value ranged from $5 million to $25 million. There is a photograph that Greene cherishes: of her as a child smiling alongside her father at a construction site. Bob did not want his daughter to see her inheritance as a given; Greene has said that her father once fired her from a job she held at the company as a teenager. But now the girl in the photograph was chief financial officer of Taylor Commercial; her college sweetheart was its president; her family was by that point living in a tract mansion in Milton, which borders Alpharetta. Who could say, of course, how regularly she made use of the indoor pool, or marveled at the built-in aquarium on the terrace level—two features of this “smart-home luxury estate,” in the words of a recent listing. But she could at least enjoy the fact of them.

Another thing I do not know about Marjorie Taylor Greene: I do not know precisely how long it was before the shape of her life—the quiet, the respectability, the cadence of carpooling and root touch-ups—began to assume the dull cast of malaise. Perhaps it was during one of the many softball tournaments, another weekend spent crushed against the corner of an elevator at the Hilton Garden Inn by grass-stained girls and monogrammed bat bags. Perhaps her Age of Anxiety arrived instead on a quiet Tuesday in the office of her multimillion-dollar company, when it occurred to her that running this multimillion-dollar company just might not be her purpose after all.

What I do know, after dozens of conversations with Greene’s classmates and teachers, friends and associates, is that by the time she reached her late 30s, something in her had started to break.

IV.

Later, on the campaign trail, Greene would anchor much of her story in the fact that she was a longtime business owner: a woman who’d always more than held her own in the male-dominated world of construction. In beautifully shot television ads, voters saw a woman whose days were a relentless sprint between building sites—hard hats, reflector vests, jeans—and light-filled conference rooms, where she wore dresses with tasteful necklines and examined important blueprints.

That is not a fully accurate picture. People at Taylor Commercial seem to have liked Greene personally, but she spent only a few years on the job and did not put her stamp on the company. Call her on a weekday afternoon, and there was a good chance she’d answer from the gym. She had “nothing to do with” Taylor Commercial, one person familiar with the company’s operations told me. “It was entirely Perry.” A 2021 article in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution noted that the Taylor Commercial website during those years scarcely hinted at Greene’s existence. The only flicker of acknowledgment came in the last line of Perry Greene’s bio, a reference to the wife and three children with whom he shared a home.

By 2011, the Journal-Constitution reported, Greene was no longer listed as the chief financial officer, or any other kind of officer. A year earlier, the company had been hit with state and county tax liens. Greene would one day joke about her lack of business acumen. But it doesn’t seem to have been terribly funny in the moment. Greene simply didn’t love the work. She had grown up with this business; she had gone to school for this business. And yet the girl in the photograph, as it turned out, had little interest in running this business.

Some people close to Greene would describe the ensuing dynamic—her own connection to the business weakening while her husband’s grew stronger—as a source of tension for the couple. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s path to Congress could perhaps be said to have begun here: when, in the aftermath of her tenure as CFO, she appeared determined to strike out in search of something to call her own.

In 2011, the same year she stepped away from her job, Greene decided to commit herself to Jesus Christ. Or recommit herself, perhaps. Last spring, Greene revealed, apparently for the first time publicly, that she was a “cradle Catholic,” born and raised in the Church. This disclosure was occasioned after Greene told Church Militant, a right-wing Catholic website, that efforts by bishops to aid undocumented immigrants reflected “Satan controlling the church.” In response, Bill Donohue of the conservative Catholic League demanded that Greene apologize. Greene felt moved thereafter to share the details of her own personal relationship with Catholicism, explaining that she had stopped attending Mass when she became a mother: when she’d “realized,” she said in a statement, “that I could not trust the Church leadership to protect my children from pedophiles, and that they harbored monsters even in their own ranks.”

Greene eventually decided to join North Point Community Church, one of the largest nondenominational Christian congregations in the country. And so during a service one Sunday, as applause and encouragement echoed across the sanctuary, Greene waited her turn to be immersed, blond hair tucked behind her ears, Chiclet-white teeth fixed in a nervous smile.

Many baptisms at North Point are accompanied by testimony, in which the congregant shares a brief word about her journey to Christ. Video of Greene’s testimony is no longer on the church’s website, but the journalist Michael Kruse described its key moments in an article for Politico. From the stage that morning, he wrote, Greene spoke about “the martyrs book,” meaning, I think, the Book of Martyrs, John Foxe’s 16th-century history and polemic on the persecution of Protestants under Queen Mary. As she’d considered the “conviction” of such men and women, “how they died for Christ,” Greene said, “I realized how small my faith was if I was scared to do a video and get baptized in front of thousands of people.” Before those thousands of people, she accepted Jesus as her lord and savior.

Greene’s congressional biography leaves the impression of deep and meaningful engagement with North Point, but according to a person in the church leadership, her involvement tapered off after several years. This person noted, somewhat ruefully, that Brad Raffensperger, the Georgia secretary of state who defied President Donald Trump, has long been involved in North Point, but “no one ever asks me about him.”

V.

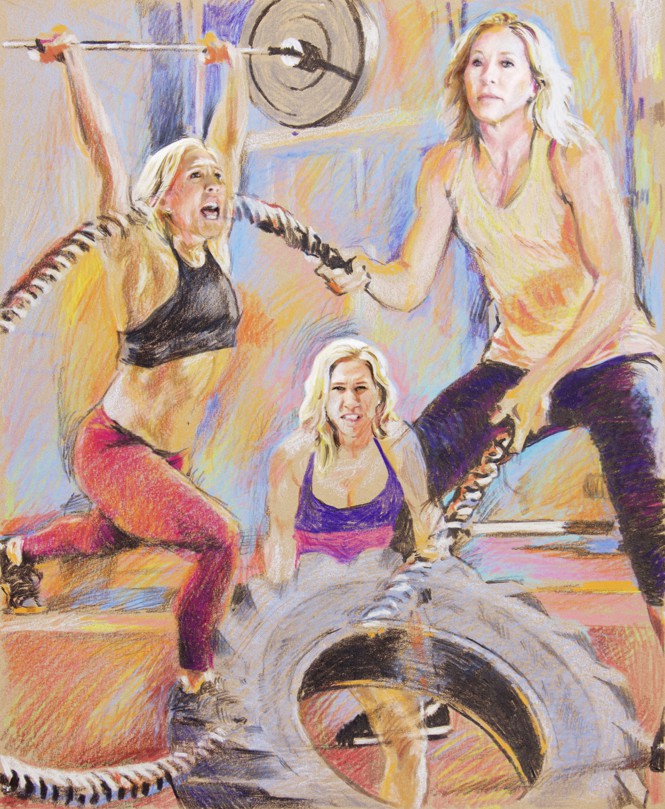

It was around this same time that Greene, as she later put it on a local radio show, “finally got brave enough” to step into a CrossFit gym. Greene’s original gym of choice had been the Alpharetta branch of Life Time. The gym, with its LifeSpa and LifeCafe, bills itself as a “luxury athletic resort,” and it’s easy to see how Greene might have tired of the ambience. She is not—has never been—the kind of biweekly gym-goer who walks for 45 minutes on the treadmill while watching Stranger Things on an iPad. In one of the few candid shots of Greene in her 11th-grade yearbook, she is flat on her back on a weight bench, lifting two heavy-looking dumbbells. “Marge Taylor pumps some Iron,” the caption reads.

In 2007, a workout partner at Life Time told Greene about CrossFit, a fitness regimen that combines Olympic weight lifting with calisthenics and interval training; it has long been popular among law enforcement and members of the military. The two women went on CrossFit.com and printed out the workout of the day, or “WOD,” in CrossFit parlance. This was, in the early years of CrossFit, how most newcomers engaged with the program, printing out the WOD and heading to their regular gym. By the end of that first WOD, Greene was sold. In 2011, she started going to the CrossFit gym in Alpharetta.

What Greene found at the gym (or “box,” as it is known) was community. The coaches, the members, the stragglers who popped in “just to see what this is all about”—they loved her. This is something many observers in Washington and elsewhere do not appreciate about Greene: that she can be extremely likable, so long as you are not, in her estimation, among “the swamp rat elites, spineless weak kneed Republicans, and the Radical Socialist Democrats who are the demise of this country that we all love and call home.” She has a sugary voice and a personable, generous affect; she is, when she wants to be, the sort of person whom a stranger might meet briefly and recall fondly to their friends as “just the nicest woman.” “The softer side of Marjorie Taylor Greene is what her friends, neighbors, and the people who elected her know,” Jamie Parrish, a Georgia Republican and close friend of Greene’s, told me. Her supporters back home can seem genuinely confused by her chilly or hostile portrayal and reception elsewhere.

At CrossFit, Greene’s warmth made her a star. “CrossFit’s really intimidating,” she explained in one radio interview. “Most people’s experience with CrossFit is … they run across ESPN, and they see these monster people doing crazy amazing things, and they’re usually like, ‘Ohhh, I’m never gonna do that.’ ” But Greene could put people at ease. When she started coaching classes herself, the reviews were stellar. “I loved working out with Marjorie Greene,” Carolyn Canouse, a former client, told me by email. “She was patient with my lack of athleticism, and always encouraging and supportive to everyone in the gym. She would bring her dog to work with her sometimes (he was adorable!), as well as her children who were all down to earth and nice to be around.”

Greene trained on most days and competed in a workout challenge known as the CrossFit Open; at her peak, she was ranked 47th in the U.S. in her age group. Over time, she seemed to regard CrossFit less as a grounding for the rest of her life and more as an escape from it altogether.

When Greene was running for Congress, a man named Jim Chambers, jarred by her self-presentation as a paragon of family values, wrote about her alleged extramarital affairs at the gym in a Facebook post. (The New Yorker’s Charles Bethea later reported on text messages from Greene apparently confirming one of the affairs.) Her first alleged relationship was with a fellow trainer. Chambers, who owned one of the CrossFit boxes at which Greene coached, recalled viewing her initially as “this married lady who was at least nominally Christian, maybe not especially, but led a very suburban life. And then, like, quickly thereafter, she confessed that her marriage was on the rocks and falling apart.” According to Chambers, Greene made no secret of the affair with the trainer. She talked openly about her problems with Perry—“different lives and interests … typical stuff,” as Chambers summarized it. “She struck me as an extremely bored person,” he added. Later, Greene apparently had an affair with another man at CrossFit, a manager whom Chambers had recently hired from Colorado; this relationship, Chambers said, was more serious, more involved, “a real affair.” (Greene’s office did not respond to a list of questions about the alleged affairs and other matters.)

By March 2012, she and Perry had separated. Four months later, she filed for divorce. Two months after that, the couple reconciled.

The family appeared to resume its ordinary rhythms. By January, Perry was posting again on Tripadvisor. This was no small thing. Before the separation, he had been in the habit of reviewing, with great earnestness, establishments ranging from the local Melting Pot (“As stated this is a fondue restaurant, so it is very unique”) to the Cool Cat Cafe on Maui (“My family loves their burgers so much we have ‘Burger Sunday’ every Sunday as our family dinner”), only to go conspicuously dark during the sadness and tumult of 2012. But come the new year he was back, sharing his thoughts about the Encore, in Las Vegas (“Great ambience. Wife and I loved it!!!”), and an Italian restaurant in Alpharetta whose wine list, he judged, was “pretty good!”

Marjorie, meanwhile, worked with a personal coach in the hope of qualifying to compete in the international CrossFit Games. For the next two years, she would busy herself with his intense weekly prescriptions, all the while chronicling her experience on a WordPress blog. “Test post,” she began in April 2013. “I’m testing posting on my blog from my iPhone … See if this works.”

Scattered among the posts about creatine supplements (“I love that stuff”) and the iPhone footage of Greene’s triple jumps, there are glimmers to suggest that her family had found its way back. “I decided that I’m going to make a little home gym in my basement,” Greene wrote in May 2013. “This way, on days I’m not coaching I can train at home and be around my kids. My husband thinks it’s a great idea. Hopefully, they can see Mom working hard, and I can set a good example for them.” Six months later: “Just hanging around the house this weekend with my family, and I’m really happy with that.”

Much of the time, however, the blog posts suggest someone pinballing from aggressive cheerfulness (“Totally doing the happy dance!!”) to the “negative thoughts” that could rush in with no warning: “I wish there was a switch to turn off those thoughts.”

VI.

“Confidence is also an area that I struggle in,” Greene wrote in one of her blog posts. “But I’ve decided to say ‘why not me?’ ”

In 2013, she set out to become a businesswoman again. Partnering with Travis Mayer, a 22-year-old coach and one of the top CrossFit athletes in the world, Greene opened a 6,000-square-foot box called CrossFit Passion, on Roswell Street, in Alpharetta. Two years later, they relocated to a space nearly twice the size. In 2016, however, Greene sold her stake. She no longer blogged about her WODs or anything else related to CrossFit.

It’s unclear what prompted so abrupt a turnaround; Greene hasn’t discussed the subject publicly. “She would go through a really hard workout and then just stop in the middle of it and start crying,” a person who was close to Greene during this time told me. “And that started happening more regularly toward the end. It was just too much stress.” (Mayer, who went on to rename the gym United Performance, which he still owns and operates today, did not respond to requests for comment.)

The other thing that happened to Marjorie Taylor Greene in 2016 was Donald Trump. Greene’s family had never been especially political. Every fourth November, minus a cycle or two, Bob and Delle Taylor made sure to stop by the library or the First Baptist Church and cast a vote. It is reasonable to assume that the Taylors leaned right. For years, the family’s construction company was a major sponsor of the Atlanta libertarian Neal Boortz’s eponymous talk show. Boortz, one of the most popular radio personalities in America during the late 1990s and early 2000s, told me that Bob (who died in 2021) had been a good friend for decades. Still, the family did not give money to candidates, Republican or Democrat; they did not hold fundraisers at the house on Lake Lanier. For the Taylors, the 2016 presidential election commenced with no more fanfare than any other. On Super Tuesday, Bob, Delle, and Marjorie did not vote in either party’s primary. In fact, Marjorie had not voted since 2010.

Greene’s political origin story was not unlike that of millions of other Trump supporters. Despite having never hinted at an interest in politics, she found herself suddenly beguiled by a feeling, a conviction that despite the distance between Trump’s gold-plated world and her own, she knew exactly who he was. “He reminded me of most men I know,” she has said. “Men like my dad.”

In some ways, he was like her dad. Bob Taylor may not have been overtly partisan, but he rivaled Trump in his tendency to self-mythologize. In 2006, Greene’s father had published a novel with the small publisher Savas Beatie called Paradigm. As best I can tell, this is Taylor’s effort to demonstrate the value of a system he invented called the “Taylor Effect”—which purports to predict the stock market based on the gravitational fluctuations of Earth—in the form of a high-stakes international caper. The story follows twin scientists who discover an ancient Egyptian box in the bowels of the Biltmore estate, the contents of which, they soon realize, could “destroy many of the world’s most powerful families” if ever made public.

He considered his stock-market theory to be “the Genuine Article”; in the afterword, he likened himself to da Vinci, Galileo, Edison, Marconi, and the Wright brothers. “History,” he wrote, “is filled with characters who endured ridicule, imprisonment, and even death because they discovered things we know today with absolute certainty to be true.” Suzanne Thompson, a North Carolina author hired to help Taylor write Paradigm, recalls that Taylor had “a bit of an exalted sense of himself.” She was unaware that he was Marjorie Taylor Greene’s father, and gasped with dismay when I told her. “Oh my gosh, I had no idea. Oh my God.”

Although Greene’s political awakening was sudden, she would later portray her support for Trump as the unveiling of a well-formed political identity that she’d had no choice but to keep hidden. “I’ve always had strong feelings about politics, but when you’re a business owner, you have to really, really be careful about what you say,” she told a conservative YouTube vlogger in 2019. But when she sold her gym, “something magically happened to me: I didn’t have to worry about what members thought anymore.”

Greene may now have felt free to speak, but it was not clear what she wanted to say. It was clear only that she wanted to say something. It was as though she spent the first six months of Trump’s administration gathering up the scattered feelings and dim instincts that informed her attraction to his brand of politics and examining them under a microscope, twisting the knob until the edges came into focus. By July 2017, Greene was ready to start posting about politics.

[Seyward Darby: There’s nothing fun or funny about Marjorie Taylor Greene]

She headed to American Truth Seekers, a now-defunct fringe-right website run by a New York City public-school counselor who went by the name Pat Rhiot. The contents of Greene’s earliest posts have been lost to the ether, but the headlines, archived by the Wayback Machine, summarize the brand Greene set out to establish from the very beginning: “Caitlyn Jenner Considering What?” was the first headline, followed over the next few days by “Female Genital Mutilation: America’s Dirty Little Secret” and “Exposed! Confidential Memo to Take Down Trump and Silence Conservatives!”

By August, when the full text of many of her blog posts become available, she was establishing her fierce devotion to gun rights and Donald Trump, and her antipathy toward conventional Republican politicians:

MAGA means get rid of our ridiculous embarrassing massive $20 Trillion dollar DEBT you put us in!! … You see we elected Donald Trump because he is NOT one of you, a politician. He is a business man, and a VERY successful one. WE elected him because he clearly knows how to manage business and money because we all know he has made plenty of it. Oh but not you people!

September saw her going after Hillary Clinton:

You know how we all have that one friend or family member that shows up to the party uninvited and just causes non-stop drama? They lie and make up stories and shift blame to everyone and everything, but constantly refuse to accept reality or the fact that maybe it’s their own fault. They ruin the party and make everyone miserable with all the crap they blubber out of their mouths, while they try to push their agenda on everyone and no one wants it. Yep Hillary. Can she just go away? Can she just go to jail?

Greene’s posts, by the standards of the 2017 far-right blogosphere, were more or less the usual fare, nothing terribly new or uniquely provocative. But Greene, in her brief time posting, had already picked up on something remarkable: People liked that she was ordinary. In the present landscape of conservative politics, ordinariness was a branding opportunity. Ordinariness ensured that even her most banal reflections would sparkle. Ordinariness allowed Greene to offer conservatives what the Alex Joneses couldn’t: affirmation that your neighborhood “full-time mom” and “female business owner” and “patriot” was fed up too. In the fall of 2017, Greene created a new Facebook page exclusively for the dissemination of her political thoughts.

The Republican base was in the market for a Marjorie Taylor Greene—a suburban woman who not only didn’t recoil from Trump but was full-throated MAGA. All over the internet, it seemed, were women who claimed to be conservative and yet could do nothing but choke on their pearls and complain about Trump’s tweets. But now here was regular Marge, who would put America first. Sweet southern Marge, who loved “family, fitness, travel, shooting, fun, and adventure,” and who, as would soon be clear, wanted very much to save the children.

VII.

Perhaps, decades from now, what will stand out most is how easily the dominoes fell.

Imagine it like this: #SaveTheChildren, right there at the top of the feed. You click on the hashtag—because who, given the choice, would not want to save the children?—and then, suddenly, you are looking with new eyes at the chevron Wayfair rug beneath your feet. It had been 40 percent off during the Presidents’ Day sale, but now you’re wondering: Had this one been used to transport a child, a trafficked innocent rolled up inside? And then not 10 clicks later you find yourself wondering about other things, too—other conspiracies, other dark forces. Because it is curious, now that you’re here, now that you’re wondering, that you can’t recall any CCTV footage of the airplane as it hit the Pentagon on 9/11. You had gone online to check if Theresa had posted photos from the baby shower and now, 20 minutes later, you log off with an entirely new field of vision, the unseen currents of the world suddenly alive.

Perhaps, for Marjorie Taylor Greene, the rug had been houndstooth and the baby shower had been Kerrie’s. But you don’t need the site-by-site search history to understand the narrative of Greene’s descent into QAnon, because the basics are so often the same.

QAnon followers subscribe to the sprawling conspiracy theory that the world is controlled by a network of satanic pedophiles funded by Saudi royalty, George Soros, and the Rothschild family. Though Republican officials have insisted that QAnon’s influence among the party’s base is overstated, former President Trump has come to embrace the movement plainly, closing out rallies with music nearly identical to the QAnon theme song, “WWG1WGA” (the initials stand for the group’s rallying cry, “Where we go one, we go all”). Yet since its inception, in the fall of 2017, when “Q,” an anonymous figure professing to be a high-level government official, began posting tales from the so-called deep state, no politician has become more synonymous with QAnon than Greene. To an extent, Greene had already signaled her attraction to conspiracy theories, questioning on American Truth Seekers whether the 2017 mass shooting in Las Vegas was a false-flag operation to eliminate gun rights. But with Q, Greene was all in. She has gone so far as to endorse an unhinged QAnon theory called “frazzledrip,” which claims that Hillary Clinton murdered a child as part of a satanic blood ritual.

Ramon Aponte, a right-wing blogger known as “The Puerto Rican Conservative,” became friendly with Greene soon after she began posting about Pizzagate, the conspiracy theory that a Washington, D.C., restaurant was involved in a Democratic-run child-sex ring. “Even though the mainstream news media ‘debunked’ it, nobody ever conducted an investigation on it,” Aponte told me. “And Marjorie Taylor Greene knew this … She was a voice for the silent majority.” (After a North Carolina man’s armed raid of the restaurant, in December 2016, Washington police did, in fact, investigate, and pronounced the theory “fictitious.”)

Was Greene a true believer? Her early outpouring of breathless posts gives that strong impression—she comes across as a convert intoxicated by revelation. But in time, her affiliation with QAnon brought undeniable advantages. It was not until she latched on to Q and Q-adjacent theories that Greene’s political profile achieved scale and velocity. The deeper she plunged, the larger her following grew. And the more confident she became.

As the months passed, she started experimenting with a new tone; she would still be regular Marge and sweet southern Marge, but she would also be Marge who told the “aggressive truth”—who wasn’t afraid to be real. In Facebook videos posted from 2017 to 2019, Greene talked about the “Islamic invasion into our government offices.” She said: “Let me explain something to you, ‘Mohammed’ … What you people want is special treatment, you want to rise above us, and that’s what we’re against.” She talked about how it was “gangs”—“not white people”—who were responsible for holding back Black and Hispanic men. She objected to the removal of Confederate statues, saying: “But that doesn’t make me a racist … If I were Black people today, and I walked by one of those statues, I would be so proud, because I’d say, ‘Look how far I’ve come in this country.’ ” The most “mistreated group” in America, she went on to say, was “white males.”

By the end of 2018, Marjorie Taylor Greene was awash in validation. Especially from men. She found herself suddenly fielding marriage proposals in the comments beneath her selfies. “Ok ok ok so you’re totally gorgeous I got that the first time I saw u,” one person wrote, “but you seal the deal with what’s in your head, I love the message of truth u bring and inform all who will listen I’M SOLD!!!” Greene, as she often would upon reading such comments, clicked the “Like” button in response.

Greene began to meet up with people from her Facebook circle. In March 2019, she traveled to Washington, D.C., as the Senate Judiciary Committee held hearings on restrictive gun legislation. At one point, in a now-infamous confrontation, Greene began following David Hogg, a survivor of the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, in Parkland, Florida. The shooting had left 17 dead, and Hogg had come to Washington to make the case for gun-control measures. Wearing a black blazer and leggings, a pink Michael Kors tote slung over her shoulder, Greene accosted the 18-year-old and, with a friend capturing the encounter on video, badgered him about his support for the bill: “You don’t have anything to say for yourself? You can’t defend your stance? How did you get over 30 appointments with senators? How’d you do that? How did you get major press coverage on this issue?” Hogg walked on in silence as Greene continued: “You know if school zones were protected with security guards with guns, there would be no mass shootings at schools. Do you know that? The best way to stop a bad guy with a gun is with a good guy with a gun.”

Greene would later trace her decision to run for office to the frustration she’d felt during that trip: No one had paid her any attention. That would have to change. As she posted on a website called The Whiskey Patriots just after the Hogg incident, and just before she launched her bid for Congress: “Let the war begin …”

VIII.

She ran and she won, of course, in Georgia’s Fourteenth District, in a largely rural outpost in the northwest corner of the state. Voters did not seem to care that Greene, who had judged the solidly conservative area to be friendlier to her chances than her home district in suburban Atlanta, had never actually lived there.

Shortly after she was sworn into office, in January 2021, her harassment of Hogg, as well as old social-media posts in which she endorsed the claim that the Parkland shooting was a false-flag operation, surfaced into public view. In her maiden speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, she set out to blunt the criticism she was receiving. Much of the speech was a disavowal of her own past statements. She conceded, for example, that 9/11 had actually happened, and that not all QAnon posts were accurate. “I was allowed to believe things that weren’t true,” she protested.

As for David Hogg, she recounted an episode at her own high school when, she said, the “entire school” had been taken hostage by a gunman—an episode that she continues to invoke as a touchstone to explain everything that is wrong about security in schools and how she has a right to browbeat a school-shooting survivor like Hogg. But if her account failed to engender much sympathy, it was because it only nominally resembled reality.

On a September morning in 1990, during Greene’s junior year, a history teacher named Johnny Tallant was holding his class at South Forsyth High School when an armed sophomore entered the classroom next door, fired a rifle overhead, and marched the students there into Tallant’s classroom; for the next few hours, the sophomore held some 40 of his classmates, and Tallant, at gunpoint. The hostages later said they were initially terrified; the student threatened to kill them if his demands for candy, soda, and a school bus were not met. Eventually their nerves quieted. Many of the students knew their captor at least somewhat, and they weren’t altogether surprised when he put down his gun and began sharing with them “everything that was going on in his head,” as one hostage recalled. “He said he wanted to get away from things and make a point,” recalled another, adding that the student had repeatedly promised not to hurt them. “He said his parents were mean, that he was tired of how they treated him, and that he had no friends and just wanted to get away.” Gradually, as police delivered the snacks he’d asked for, the sophomore let most of the hostages go, including all the girls but one, who knew the student well and stayed behind to keep talking to him. Five hours in, when the remaining hostages moved to grab his gun, he did not resist; when the police burst in moments later, he did not fight back.

Tallant recalls that Greene reached out to him sometime before she launched her bid for Congress, in the spring of 2019. He had no idea who she was, or why she was calling him at home. He listened that day as the unfamiliar woman explained that she wanted to speak with him about the events of 1990—that she’d been a student at South Forsyth when everything happened. Still, Tallant struggled to place her. Greene had not been in his classroom. Everyone else at the school, including Greene, had been quickly evacuated and bused away. Tallant was taken aback by Greene’s intensity, her apparently sudden need, decades later, to discover flaws in the school’s handling of things: “She was asking me some crazy questions about—she was saying we should have had guns ourselves, you know … She sounded like kind of a nut.”

Tallant would not give her what she wanted. “I told her right off, we didn’t need guns,” he said. It wasn’t a political statement; for Tallant, it was just reality—the only conclusion you could draw if you took care to examine the particulars of the crisis, of the teenage boy at the center of it. The sophomore was known by classmates and teachers to struggle with seizures and other symptoms of epilepsy. As one of the hostages later put it: “I wasn’t scared of him. I was scared of what the police would do when he stepped into the hall, and I was afraid of what the police were planning to do as he walked from the room to the bus.”

But never mind. Greene hung up with Tallant and eventually proceeded with her preferred version of the story in her speech on the House floor: “You see, school shootings are absolutely real,” Greene said, her navy face mask emblazoned with the words FREE SPEECH in red letters. “I understand how terrible it is because when I was 16 years old, in 11th grade, my school was a gun-free school zone, and one of my schoolmates brought guns to school and took our entire school hostage.”

“I know the fear that David Hogg had that day,” she pronounced. “I know the fear that these kids have.”

Did it even matter that Greene had not been taken hostage, or that the episode had been handled wisely and without bloodshed, or that the teacher in the classroom had told her she was wrong about her memories and her conclusions? By now, it may have occurred to Greene that performance was enough. That politics might in fact be that easy—as long as you were angry, or at least good at acting like it, most people wouldn’t bother to look beneath the hood.

IX.

In late September 2022, Perry Greene filed for divorce from Marjorie Taylor Greene on the grounds that the marriage was “irretrievably broken.” His timing—so close to the midterm election—did not go unnoticed in Georgia political circles. Six weeks later, on November 8, Marjorie easily won reelection to her second term in the House of Representatives.

Given her popularity among a segment of the Republican base, she is certain to play a major role in the GOP leadership, whether that role comes with a specific title and assignment or not. She wields power much like Donald Trump, doing or saying the unthinkable because she knows that most of her colleagues wouldn’t dare jeopardize their own future to stop her.

[Barton Gellman: The impeachment of Joe Biden]

What Marjorie Taylor Greene has accomplished is this: She has harnessed the paranoia inherent in conspiratorial thinking and reassured a significant swath of voters that it is okay—no, righteous—to indulge their suspicions about the left, the Republican establishment, the media. “I’m not going to mince words with you all,” she declared at a Michigan rally this fall. “Democrats want Republicans dead, and they’ve already started the killings.” Greene did not create this sensibility, but she channels it better than any of her colleagues.

In her speech at the Cobb County GOP breakfast, Greene bemoaned “the major media organizations” for creating a caricature of her “that’s not real” without ever, she said, giving her the chance to speak for herself. Afterward, I introduced myself, noted what she had just said, and asked if she was willing to sit down for an interview. “Oh,” she said, “you’re the one that’s going around trying to talk to [all my friends]. This is the first time you’ve actually tried to talk to me.” I explained that I had tried but had been repeatedly turned away by her staff. “Yeah, because I’m not interested,” she snapped. “You’re a Democrat activist.” Some of her supporters looked on, nodding with vigor.

Whether Greene actually believes the things she says is by now almost beside the point. She has no choice but to be the person her followers think she is, because her power is contingent on theirs. The mechanics of actual leadership—diplomacy, compromise, patience—not only don’t interest her but represent everything her followers disdain. To soften, or engage in better faith, is to admit defeat.

I think often of Greene’s blog post from July 26, 2014, and the question she posed to herself during her crisis of confidence. “Why not me?” she had written tentatively, trying it on for size. I think of it whenever I see Greene onstage, on YouTube, on the House floor, making performance art of rage and so clearly at ease with what she is. Were the question not in writing, I’m not sure I’d believe there was a time in her life when she’d been afraid to ask.

This article appears in the January/February 2023 print edition with the headline “Why Is She Like This?”