America has botched its coronavirus response in so, so many ways since the pandemic began. Even in a country that stands apart from the world for its horrific failures, there have been as many leadership bungles as there are states: Some failed to heed early warnings. Others refused to learn the lessons of outbreaks that came before theirs. Still others played politics instead of following science. And then there’s Georgia.

Georgia’s response to the pandemic has not been going well. It was bad from the beginning: Back in early April, weeks after other states took initial precautions, Georgia dawdled toward a shutdown while its coronavirus cases surged. Still, less than a month later, the state chose to be among the first in the nation to reopen, bringing back businesses known to accelerate the virus’s spread, such as restaurants and gyms, even though new infections had never made a significant or sustained decline. In June, the state welcomed back bars. What happened next was predictable, and was predicted: Case counts came roaring back. More people got sick and died. Many of these deaths were preventable. The state now has the sixth-highest number of coronavirus cases in the United States, behind five states with significantly larger populations.

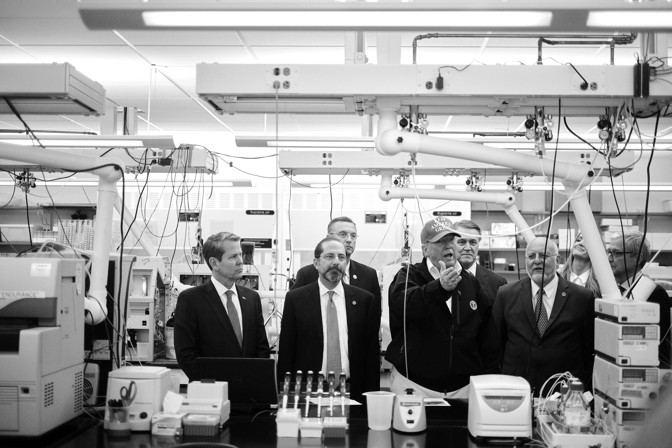

Lots of states—such as Florida, California, and New York—have mishandled the pandemic since it hit in March. But when you look closely at Georgia, you see a state with a leader unique among his peers. First-term Republican Governor Brian Kemp presided over a late shutdown so short that his reopening drew a public rebuke from President Donald Trump, who has frequently opposed shutdowns altogether. Kemp’s administration has repeatedly been accused of manipulating data to downplay the severity of the outbreak. He has sparred publicly with the state’s mayors and sued to stop them from implementing safety restrictions or even speaking to the press.

To understand the course that Georgia has plotted through the pandemic, you have to understand Kemp’s failures. Those same failures, and the trajectory of the state governed by them, also represent a microcosm of America under Trump. The governor has demonstrated a willingness to defer to the president instead of his own constituents, sacrifice Georgians’ safety to snipe at his political foes, and shore up his own power at the expense of democracy. In short, Kemp is a wannabe authoritarian, and millions of Georgians have suffered as a result, with no end in sight.

Kemp has emulated strongmen since he entered state government. In 2018, as Georgia’s secretary of state, Kemp administered his own election by a thin, contested margin, despite calls to resign the office before running for governor. In his previous role, Kemp systematically purged more than 1 million voters from the state’s rolls, disproportionately disenfranchising Georgians of color. More than half a million of those voter registrations were voided in July 2017 alone, months into Kemp’s campaign for governor. Kemp’s office did not respond to a request for an interview, but in the past, he has repeatedly denied that these actions amounted to voter suppression.

In Georgia, and around the world, it has become clear that a novel virus doesn’t respond to the anti-scientific, expertise-shirking preferences of modern authoritarianism. When Kemp announced the closure of the state’s nonessential businesses on April 2, he said it was because he had learned something game-changing about the virus: that it is transmissible before an infected person develops symptoms. In reality, that had been a widely accepted belief for weeks, one that had helped encourage earlier lockdowns around the country. And unlike other states that were slow to shut down, Georgia already had a raging outbreak of nearly 5,000 identified cases. In southwest Georgia in late February, a funeral in the small, majority-Black town of Albany set off a chain of infection that sickened hundreds of people and left the local hospital system overburdened and overpaying for low-quality protective gear.

[Read: Georgia’s experiment in human sacrifice]

If a slow shutdown had been Kemp’s only major fumble, he’d be in broad and ideologically varied company both nationally and internationally. Instead, he has continued to double down on the state’s approach to the virus in ways that mirror not just Trump, but authoritarian leaders overseeing poorly controlled outbreaks all over the world, such as Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and India’s Narendra Modi. He has also taken a more hard-line stance than most of his Republican peers. GOP governors in Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas have implemented statewide mask rules in response to worsening outbreaks, and others who haven’t, such as Ron DeSantis in Florida and Doug Ducey in Arizona, have still allowed cities and counties to enforce their own local requirements. Not only has Kemp repeatedly refused to require masks in Georgia, but the state’s current pandemic emergency order was written with an explicit restriction to prevent local leaders from implementing their own mask rules.

Kemp’s administration has gone so far as to sue Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms over the city’s mask mandate and its plan to roll back the city’s reopening to its earliest stage, closing bars and restricting restaurants to takeout. When Bottoms fought the lawsuit, Kemp sought to stop her from speaking to the press. Other cities in the state, such as Savannah and Athens, also passed their own mandates but escaped inclusion in the lawsuit, which has pushed some to question whether the governor was trying to punish Bottoms for her support of Joe Biden. A Kemp spokesperson told The Washington Post that the lawsuit was primarily about the new restrictions on businesses in Bottoms’s order, which weren’t present in other municipalities’ mask mandates, but as the paper pointed out, masks were listed as the first issue in the complaint. “One has to ask about the political aspect of a conservative southern governor and a strong supporter of the president having a very public legal action against the Atlanta mayor, who’s been a vocal supporter of Joe Biden,” Harry Heiman, a professor at the Georgia State University School of Public Health, told me. Kemp backed down from the lawsuit last week, and Atlanta’s local mandate remains in effect.

None of Kemp’s actions has been popular among the state’s residents. According to findings released last week by the Atlanta-based market-research platform 1Q, 73 percent of Georgians surveyed believe that cities should be able to enforce their own mask mandates, and 70 percent disagree with Kemp’s refusal to institute a mandate statewide. In recent months, his overall approval rating has taken a hit. In May, Kemp was the only governor whose coronavirus response was less popular than the president’s among his own constituents. A recent poll pegged Kemp’s approval rating at 43 percent, down from more than 59 percent in January.

Kemp, like Trump, has recently started to encourage mask usage while still aggressively opposing any kind of enforceable mask rule. The problem with that approach, according to public-health experts, is that it sows confusion, making it more difficult for people to feel confident in their safety. The state’s own messaging has at times been misleading in other ways. On its Department of Public Health website, the state spent months backdating cases to a patient’s first symptoms, which meant that the most recent two weeks of the graph always looked as if the pandemic was in marked decline. The state has also released misleading graphics that it later insisted were honest errors in data rendering, such as a bar graph of case counts with the dates out of chronological order, again depicting a nonexistent downward slope.

In mid-July, two nearly identical maps of Georgia’s coronavirus outbreak began circulating on Twitter, depicting the state’s outbreaks on July 2 and July 17, over which time cases increased significantly. Both maps show only three of the state’s 159 counties shaded in red, marking the most dire spread of the disease. As case counts exploded, the state had raised the number of cases required for a county to change color. Once local media took notice, the state redesigned its map. The public health department’s website also now allows users to sort new coronavirus cases by date of diagnosis, the method used almost exclusively in other government and media visualizations of the pandemic.

[Read: Keisha Lance Bottoms: Atlanta isn’t ready to reopen—and neither is Georgia]

Then there is the matter of reopening schools. The state’s accelerated reopening spiked cases just in time for the South’s typically early school calendar to begin, leaving educators, parents, and students to fend for themselves as Kemp urges the resumption of in-person instruction in order to protect kids from non-coronavirus threats such as malnutrition and abuse. But if Kemp’s concerns lie with the safety of the state’s children and the importance of getting them back in the classroom, why didn’t he do more to stop the spread of the virus? Why, instead, did he prioritize sending low-wage workers back to their jobs in bars, restaurants, nail salons, and gyms?

Some of Georgia’s school districts opened this week, and already the system is buckling under the weight of infection: Yesterday, we learned that the state’s outbreak had claimed its youngest victim yet, an otherwise healthy 7-year-old boy. One Cherokee County elementary-school class has already had to be quarantined after a second grader received a positive test result on the first day of school. Earlier this week, a photo from inside North Paulding High School in exurban Atlanta showed a crowded hallway with few teenagers wearing masks. An outbreak has already sickened members of the school’s football team, and students say they fear expulsion if they don’t show up. Two students were suspended for distributing photos of the school’s lax safety measures; at least one of those students has been reinstated following a public outcry over her right to free speech.

Georgia’s public universities, which are preparing for students to come back over the next couple of weeks, provide a bleak view of how the state is managing the dangers that a return to regular life presents for Georgians. For much of this summer, the University System of Georgia refused pleas from faculty and staff to require students to wear masks to class, or to allow individual colleges to make their own mask rules, before eventually relenting and requiring masks. At the University of Georgia, freshmen will still be required to live in cramped on-campus housing, much of which assigns two students to one privacy-free room, even if their classes are remote. For students who attend instruction in person, photos have begun to circulate on social media of the safety measures that await them: a small plexiglass divider loosely affixed to the front of a teacher’s classroom desk, or every other urinal in a public bathroom marked off with painter’s tape. With the majority of students yet to return, UGA already has the third-largest campus outbreak in the country, and Athens, the town where the school is located, ran out of intensive-care beds last week.

[Read: ‘This push to reopen schools is guaranteed to fail’]

Despite all his mistakes, it’s not too late for Kemp to wrangle the pandemic, said Heiman, the Georgia State professor. He told me that a statewide mask mandate; closing bars, gyms, and indoor dining; and clear, consistent messaging from state leadership about pandemic safety can work quickly to limit transmission of the virus, just as such measures have in New York, following that state’s catastrophic outbreak. Once transmission is low, more businesses can be safely reopened, testing supplies and personal protective equipment can be stockpiled, school buildings can be altered for better ventilation, and life can return to something closer to normalcy while Georgians wait for treatments and vaccines to come along.

In order to do that, though, Kemp would have to do something authoritarians hate: admit he was wrong, and change his mind based on evidence, the advice of experts, and the will of the people. The same is true for the country as a whole. America is a few decisions away from a much different future.

Instead, like the authoritarian he’s shown himself to be, Kemp seems intent on maintaining the disastrous course his administration has plotted so far, at the expense of the people of Georgia. “It’s truly unbelievable,” Heiman said. “It will be a case study for decades to come of what an utter collapse of political and public-health leadership looks like.”