Once upon a time, there was a guy who had a really great collection. He had a bunch of really, really great old stuff — not like that crap in your collection, all that stuff you keep out in the garage, those cardboard boxes packed solid with your formerly impressive accumulation of CDs. Sorry, but nobody really cares why you’re still hanging on to that pinewood derby pseudo-Stratocaster you hacked out with a jig-saw for a C-minus back in high school wood-shop. It’s gnarly, but only in the pathetic sense.

Because this guy, the guy with a really great collection, he actually owns one of Jerry Garcia’s guitars, “Tiger,” the one from the ‘80s with Jerry’s custom-built secret stash compartment. The guy’s got the actual black Stratocaster — a real one — that David Gilmour played on Dark Side of the Moon and The Wall. At 3.9 million bucks, it was, if only for a brief couple of years, the most expensive guitar ever. Until the guy with the great collection paid even more for a Fender Mustang. Only not just any Fender Mustang, but one that Kurt Cobain flung around in the artificial video fog of “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” That one cost $4.5 million, which now is not the most ever paid for a guitar, or even the most ever paid for one of Kurt Cobain’s guitars, but is most definitely the most ever paid for a Fender Mustang.

This guy’s really great collection isn’t only just really great guitars. Like after Christine McVie passed away, he honored her death by scooping up her former husband John McVie’s bass, the exact same one used on Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (you’ve heard of that, right? Sold almost as much as Dark Side of the Moon) snapping it up for a piddling $100 grand. A major bargain, and a whole lot less than someone else paid for the pair of wooden British toilet-chain balls that dangled between Mick Fleetwood’s lanky legs on the cover of Rumours (you’ve seen that cover, right?) What’s more, the guy’s got a bass drum-head with “The Beatles” logo from back when they played The Ed Sullivan Show, and then a Ludwig drum set from Ringo that it pretty much fits. Since the guy already had guitars from John, Paul, and George, he couldn’t help himself: He contacted the Associated Press, and told them, “Finally, after 45 years, the Beatles are together.” And you’ve heard about Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, right? Kerouac blazing away, typing it single-space on a single 120-foot-long roll of paper, bashing it out on benzedrine, bebop and brilliance for three single-minded sleep-free weeks without ever having to yank out a single typed page or feed fresh pages in — well, after coughing up $2.43 million, the guy with the great collection owns that original scroll too. All except for the part at the very end that Kerouac’s friend’s cocker spaniel chewed off and swallowed. (You know how cocker spaniels are, right?)

“Searching for Jack Kerouac and Andy Kaufman…missing Tom Petty and Kobe…but this old river keeps on rolling though…the streams thin out and runs to dry…but the Magic forever remains.”

– tweet from Jim Irsay, July 16, 2021

In the immortal words of Ray Wylie Hubbard, some things are just cooler’n hell — regardless of who used to play ‘em once upon a time, or who currently owns ‘em. Like Stephen Still’s tweed Fender Bassman amp, which he’s had for 30 years, when it already had 40 years of mileage. You know how those old fabric-covered tweed Fender amps get all ratty at the edges and unraveled at the corners and all tattered and beat-to-shit from roadwork and life? Well, this one’s worse. It’s rattier and a lot more unraveled than any of ‘em ever, and it sounds like a million bucks.

It sounds like 10 million bucks right here in rehearsal, where Stephen Stills is burning. He’s burning like a dude who used to get handy personal guitar tips direct from his pal Jimi Hendrix, with that raggedy-ass tweed amp barking like a Doberman. Your pinned-back ears abruptly remember that Stephen Stills used to be known as a scorching guitar god. He seems to be remembering the hell out of it himself — right here and right now, in rehearsal, in front of a band that’s sticking to him tighter than his shadow. That sound — that sound lures you up to the apron of the stage, squaring off precisely in front of that barking tweed amp so you can later on get around to asking what brand of hearing aids Still is rocking these days. (Duals, actually; recommended by Neil Young.)

Truth be told, Stephen Stills is looking even more significantly ragged than his amp: Short and stout, shiny bald spot in the back, decked out in a worn-down flannel shirt that he surely fished out of Neil Young’s donation cast-offs, he’s making that ragged-but-righteous tweed Fender scream like a fresh-oiled chainsaw, chips and sawdust flying. He’s rehearsing a slow saw-ripping version of “For What It’s Worth” — a 56-year-old song he wrote when he was 22, a song of confusion then and now —backed by a band of deadly ringers, double-scale session cats and studio stars of the highest order, and they’re all rehearsing here onstage in San Francisco’s Bill Graham Civic Auditorium.

Got that? Tonight they’re using the SF Civic as a doggone rehearsal hall, with all the attendant dozens of indoor and outdoor security guards and teams of facilities management functionaries and hall staff and sound and lighting crew soaking up overtime salaries as if it were show-time… And the guy with the really great collection footing the bill.

Stills comes off his third round of fresh improvs, going head to head with Kenny Wayne Shepherd, sweating like a racehorse, winded and wrung out. “It’s not that I’m old and fat,” he dryly assures the band cats, panting. “It’s the Covid…” He’s old and fat, recovering from Covid, 14 months sober, wheezing a little, kicking ass.

These cats in this band, The Jim Irsay Band, are ridiculous monsters. Kenny Aronoff on drums — how do you smack that hard and make it subtle and supple all the same? How’d he do that? And the other Kenny, Kenny Wayne Shepherd, formerly one of those older-than-his-teen-years white blues guitar whiz-bangs, appears to have fallen backwards down the deep well of tradition and come out on fire. And then there’s Bukovac. Tom Bukovac has won Nashville Session Guitarist of the Year so many times in a row they probably retired the bowling trophy. Over and over, on the sudden drop of somebody else’s dime, these guys build glorious head arrangements out of loose talk, wicked chops, whimsy and spit. Bukovac is the super-glue between all the joints, sewing all this masterful badassery together without a seam or a loose stitch. It’s magic, it’s miraculous how quicker than quick these guys whip these songs up out of nowhere — impromptu on-the-spot arrangements that instantaneously sound majestic, like somebody’s lavishly-produced live-in-concert recording. Which is, I guess, pretty much totally what this is, sort of. In a way. In a weird way.

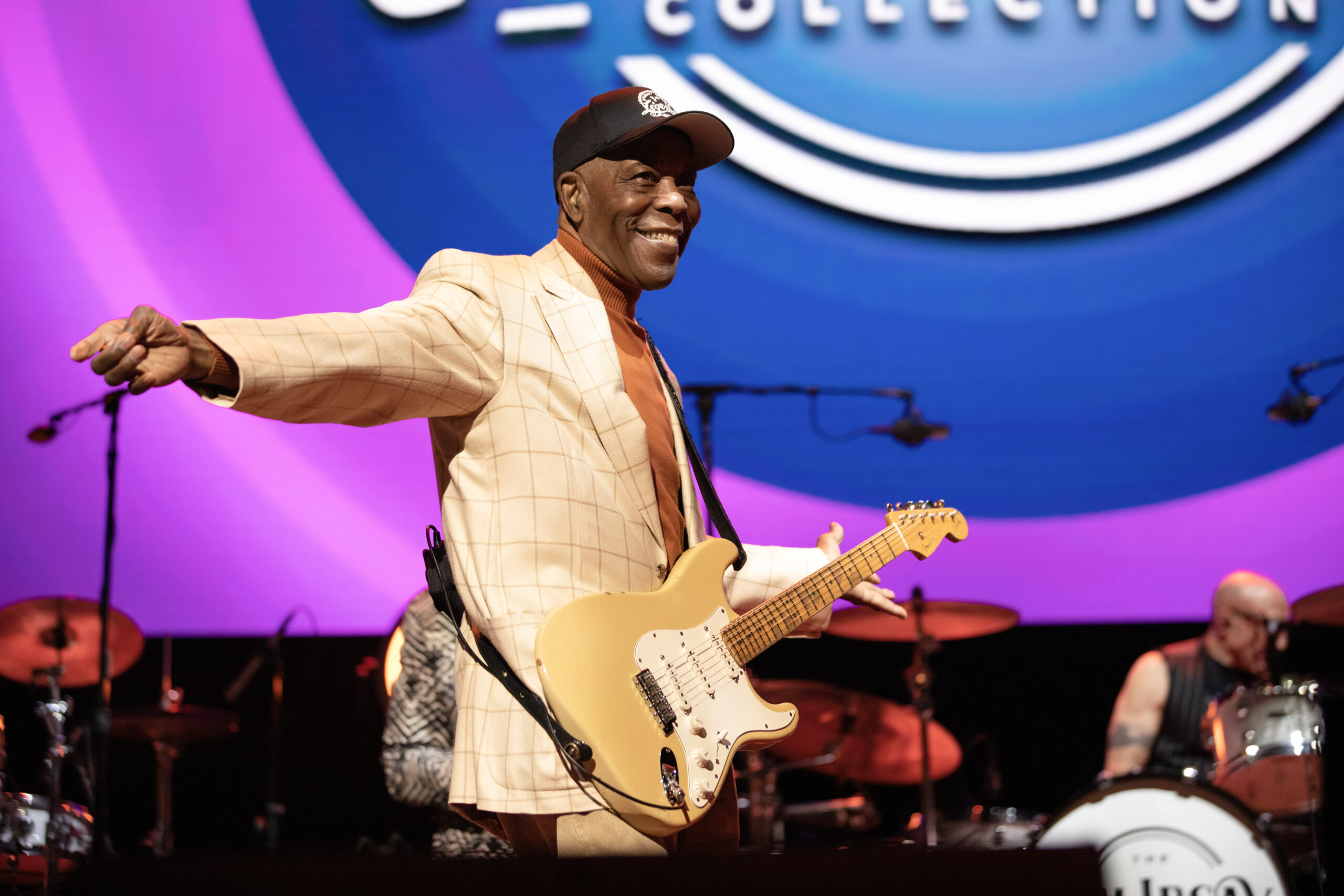

What this is, actually, is the All-Time Ultimate Dad Band, yanked out of the three-car garage and flown on private jet to the fantasy stage of the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, a 7500-seater with lights and cameras and catering and security and custom Diamond Vision displays and an open bar, with both the two killer Kennys and a Bukovac, and R.E.M.’s bass-player Mike Mills due to arrive, with Buddy Guy and Chicago blues harp master Billy Branch, and, swear to God, John Fogerty, plus a symphony orchestra string section, some more guitar and keyboard players, the original drummer from Paul McCartney’s Wings, a fiddle/mandolin multi-instrumentalist singer, a four-piece section of female backing vocalists, and just the kind of dreamed-up Dad Band cover-song set-list you can guess wearing a blindfold. Oh, and plus, unforgettably, Ann Wilson —because who the hell would you rather hear yowl Led Zeppelin’s “The Immigrant Song” fronting these monster cats than Ann Wilson? Seems a pretty safe bet that Robert Plant would prefer it, too. Probably even more true for Jimmy Page.

Seated nearly hidden in a chair at stage left, just past the drum riser, Ann Wilson is casually nailing it — as in compressed-air power-nail-gun nailing it —with finesse. In a chair. They’re starting to work up “Rock and Roll,” and Bukovac tells her she can just talk her way through the lyric if she wants, maybe save her voice as they run through it. From a mile away, from up where the cheap seats would be if they were going to charge for this gig, you can see it: Ann Wilson isn’t about to talk her way through Zeppelin’s “Rock and Roll.” She’s a nail-gun, poised to pound this thing in place perfectly, nail it straight with full-on style flourishes and filigree, even just in early rehearsal mode, all the while simply sitting there mildly, the air-hammer of the gods, in what’s either a lawn chair or a throne. When a great singer sings, rips a hole in the atmosphere, something inexplicable happens. Great singers sound different than the rest of us, in ways that defy measure or even much understanding.

It’s like that a lot — a whole lot, repeatedly. The band is ungodly, snatching up a standard Dad Band setlist of songs by Zeppelin, Floyd, the Stones, Fleetwood Mac. Elton John, Neil Young, and the Dead, and pumping fresh life into them, making them rise up from folded-away flatness like it was Thanksgiving Day at the Macy’s parade, and now you’ve got to hold ‘em down with ropes. The only thing missing is Jim Irsay.

It’s Friday night, and getting late. Crew started load-in on Wednesday. There’s a lot to load-in, a tremendous amount to unpack and set up, far more than most rock shows. There’s the great collection — The Jim Irsay Collection, it’s titled — and all its custom display cases and their lights, and all those huge, highly illuminated signs spelling out Jim Irsay’s stylized signature logo, so you’ll know for certain that what you’re gawking at is The Jim Irsay Collection. Great blocks of TV commercials have been airing steadily for weeks, inviting one and all to come hear The Jim Irsay Band, one night only, every ticket free on Eventbrite. Doors open Saturday at 6 pm, so the public can stare at all the really, really great stuff Jim Irsay has collected. Did you know he has a marked-up galley copy of Alcoholic Anonymous’ Big Book? And the glasses Mike Myers wore in the Austin Powers movies? A Wanted poster for John Wilkes Booth? Sylvester Stallone’s script notes for Rocky? The show is scheduled for 8pm, so the assembled audience can experience The Jim Irsay Band in all its glory, all its grandeur, all its grandiloquence. And look — here comes Jim Irsay onstage now.

“Jim Irsay is widely known as NFL royalty, the eccentric billionaire owner of the of the Indianapolis Colts.” — Forbes, December 8, 2022

Jim Irsay owns the Indianapolis Colts. He inherited his NFL team from his father, Robert Irsay, whose own mother called him “a devil on Earth,” (and in Sports Illustrated, no less). Jim Irsay tells me his father was “a malignant alcoholic.” Robert Irsay bought the LA Rams and traded them the same day for the Baltimore Colts. Notoriously, after years of raging controversy, firing coaches and calling plays from the sidelines, Robert Irsay loaded up a fleet of moving vans in the dark of night and hauled the Colts away, leaving Baltimore stunned as he took what you might call The Robert Irsay Collection to Indianapolis overnight. He threw marvelous gift-laden parties, lavish affairs with full orchestras.. The way Jim Irsay tells the story, when he inherited the Colts and his father’s businesses, they were drained of all value and practically worthless — though Jim Irsay had been the Colt’s General Manager since he was 25 — and so he personally built everything back up again all by himself. (The way the Forbes 400 list tells the story, Jim Irsay rates a bottom-scraping 2 out of 10 on its Self-Made scoring, and an even lower 1 as to his Philanthropy rating.) He convinced the county and the state to build his Colts a brand new stadium, complete with retractable roof, at a cost of $719 million. An oil company paid $122 million for naming rights, while the Colts pay the annual rock-bottom rent of $250,000 (that’s $21,000 a month, for a 70,000 seat stadium) scooping up all football-related profits — like tickets, like parking, like concessions, like merchandise and like well-upholstered corporate sponsorships and private sky-boxes, all of which are said to total up, conservatively, to a tidy $30 million per year.

These days Forbes reckons Jim Irsay is worth $3.9 billion, give or take a guitar or two. The city of Indianapolis has asked him for financial help in keeping the lights on and the roof retracting, but he’s got ‘em over a barrel — remember the Baltimore Colts? Remember the Forbes Philanthropy score? — and he’s refused, flashing that big 2006 Super Bowl ring of his. Jim Irsay has the Colts logo tattooed on his right shoulder, but it doesn’t specifically spell out Indianapolis.

Jim Irsay isn’t publicity shy. When he bought Kerouac’s On the Road manuscript, he commissioned photos of himself wrapped with the precious scroll, draped around his body. In just the last few weeks, Irsay made headlines for publicly suggesting the owner of Washington’s NFL franchise ought to be unceremoniously ousted from the league, although just a few weeks later he’d changed his mind again. Next, he abruptly fired the Colts’ coach, replacing him with a former Colts center whose previous coaching experience had been at the Hebron Christian Academy of Dacula, Alabama. Within a few weeks, the Colts set an historic 102-year NFL record for humiliating collapses by losing a game they had been winning 33-0 at halftime. Somewhere along in there, Jim Irsay announced that he was producing his very first Hollywood movie, about a good-girl singer-songwriter in love with a bad-boy rock star. He’d already commissioned a documentary about himself, and the film’s crew was trailing him everywhere, tracing his every step, making sure never to miss a moment of the rich pageant of Jim Irsay’s life, other than those rare milli-moments when he needs privacy. (There’s a video of the Colts owner, helpfully tweeted from his own Twitter account, of Jim Irsay offering a spirited rendition of Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” while parked mid-flight on the toilet of one of his four private jets.)

He’s every bit as forthcoming about his lifelong drug and alcohol abuse problems, if necessarily so, since years after he declared himself free of his addictions, he was found in his car with a laundry bag loaded full of pills, and $29,000 in loose change. Charged with four felony drug counts and a misdemeanor for driving under the influence, the felony charges were dropped when Irsay managed to provide documents that suggested the pills were legal. Not the most difficult documentation for a pro football team owner to achieve, perhaps — an Indianapolis pharmacy had once filled 120 prescriptions for him in a single year — but the NFL suspended him for six games anyway, and fined him $500,000, while the Colts soldiered on in his absence. Nowadays, he proudly calls himself a former junkie.

It wasn’t mentioned in all those TV commercials, but behind the scenes, The Jim Irsay Band show has a backstage story to consider. The Jim Irsay Collection was set up as a traveling roadshow, and it had hit seven previous cities at sporadic intervals separated by months, making no bones about the fact that Jim Irsay had gone fishing, dangling his pop-up mini-museum as bait. He was looking for the right city to make an offer, to cut a deal, to build him a museum — retractable roof not necessarily required — for The Jim Irsay Collection Of Really Great Old Stuff. Throwing a free show stacked stiff with his collection of famous Golden Age rock stars wasn’t the dumbest way to draw a crowd and bait the hook.

“What can I say? I could say something, but nothing IS something; nothing isn’t nothing, if I say it; it’s something. No things are nothing things.” – Jim Irsay’s first tweet to Colts fans upon return from his NFL suspension

Late in the rehearsal Jim Irsay shows up, old bones shuffling slowly, taking the same seat on the stage Ann Wilson had used, but shoved forward, right in the thick of things. He wears a suit and tie, dark sunglasses, and one of those hats that American male senior citizens invariably wear on their world travels, the ones that match the fanny pack. He’s jovial. He’s forthright and outspoken. He’s the center of all attention. He’s loud.

Onstage, in the flesh, Jim Irsay could be a near relative of W.C. Fields, perhaps a grand-nephew, if slightly less nobly endowed of nose, and lacking Fields’ mellifluous, unctuous, larcenous voice. Jim Irsay’s voice is a rusty, dusty, raspy thing, but even when just merely speaking, microphone or not, he makes up for it by being loud and forthright, then forthright and loud. When, upon arrival, he’s not talking, he’s reading lyrics out loud — loudly — off the teleprompter, no matter in the least, not at all, if he fits with the section of song the band is working up. “He’s a different guy, isn’t he?” his friend Jerry asks, flown in from LA, and already knowing the answer.

Out of nowhere, Jim Irsay is seized, grabbed, goosed by a sudden great idea — an inspired genius idea. He’ll sing Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In The USA” at tomorrow night’s show because… well, because it’s a genius idea, because he just suddenly thought of it, because he’s calling plays heroically from inside the huddle, because he’s in the mood.

The band straps the song together almost instantaneously — the genius part may be that “Born in the USA” only has two chords, and is unencumbered by much melody. All that’s left for a singer to screw up is rhythm and pitch and timing and musicality and dynamics and sensitivity to the lyric and to the band. Admittedly, none of those are Jim Irsay’s great strengths. Under the circumstances, his greatest strength may be that it’s a fine time to be a billionaire.

The problem with genius is that it is so rarely satisfied. The band slaps down a roaring “Born in the USA,” suitable for a king or a Springsteen, but Jim Irsay knows where the whole thing has gone all wrong, where it’s simply not up to his standards. “Band! We are not playing folk music here!” he bellows at them. He’s stood up now, rising from his chair, stepping away from his teleprompter to make his point. “This is probably the greatest song ever recorded!” So, naturally, he wants them to really lean in on it, harder! — you know, the way he leans in harder, lots harder when some stray hunk of lyric rolling by on the teleprompter — dead man’s town, or end up like a dog — inspires him to really bray, really lean on that drama-dripping hunk of words, the way he’s braying and bellowing and leaning on the band right now. You know, the way a great coach totally inspires his football team by bellowing at ‘em in the locker room. His father, tearing the team a set of new ones in the locker-room, once upon a time made one player stand in the corner like a child.

You’d swear Kenny Aronoff couldn’t hit a snare any harder, but he can. The song isn’t fit for a king any longer, and it’s difficult to imagine Springsteen rousing that much anger. Whatever was right about the earlier version might still be there but it’s louder and angrier this time, ruder, ruled by Kenny Aronoff smacking that snare like somebody has just slapped him with a subpoena. It isn’t a better version, it’s a cruder one, and Jim Irsay is terribly satisfied when it’s done. Then, before the rehearsal is over, inspiration strikes again. He decides to toss out “Born in the USA,” so he can sing “Born to Run” instead. Genius is so rarely satisfied.

“History is so important… We’re always seeking. I see the seekers in my mind walking across the old beautiful lands of this country 300 years ago, not with muskets, but with guitars slung over their backs. Because to me, that’s really what it’s about.”

—Jim Irsay, Guitar.com, December 31, 2021

When Jim Irsay finally shows up for Saturday night’s pre-show press conference, the various and sundry rock stars and celebrity musicians — with one notable exception: John Fogerty, unaccustomed to being placed on display — are brought out and assembled in an orderly line behind him, like a police lineup without the height markers. On the drive over from the Four Seasons, Kenny Aronoff quoted “Let It Bleed,” by the Rolling Stones, so after the announcement of charitable donations, the press conference kicks off with Jim Irsay yowling “We all need someone we can lean on….” It’s loud, but doesn’t seem like he’s heard the tune.

Prompted by not much more than a microphone, a row of rockstars stacked behind him, and a rapt audience of alleged representations of the press, Jim Irsay will reveal to one and all the true meaning of Bob Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone.” (Greil, if you’re listening, please take notes.) He went on at astonishing length, as he does, swerving lane to lane, as he does, but basically it turns out that “Like A Rolling Stone” has nothing to do with a humiliating tumble from wealth and riches, or being bound to fall from the lush life and the boon companions, forced to live on the street and get used to it, cast down among the unknown, the unknowables, the untouchables you’d laughed at once upon a time. Nope. Turns out it’s all about America saying “Screw you!” to England.

He’s got a real cowboy hat with cavalry cords on tonight, suit and tie and those impenetrable shades. “I know my mind is sometimes hard to follow,” he starts, endearingly. “I have trouble following it too. But…if you just all take a shot of Patrón, you might understand what I’m about to talk about.” [Cheers, and a renewed rush on the bar.]

What he was about to talk about was a long series of double-shots poured steadily, rapidly, unceasingly, one after another, into a thimble. “Two of the greatest American artists, poets, of our time, that were left unstrung by Johnny Cash, Woody Guthrie, Martin Luther King…first, first, um, when Bob Dylan came in and wrote like “Like A Rolling Stone,” it was basically to England and… and… and telling them how does it feel, you know, you tyrannical sons of bitches! [he laughs] Sorry, I know we have a lot of Londoners here — though not right up next to me… when he wrote that, when he wrote that song, to me that was kind of a huge, a huge part in our history of great writers in the 20th Century and after that when, when Bruce Springsteen came along a few years later and wrote “Born to Run,” I just wanted to take you through for a couple seconds, you know, kind of why we’re here and um, really what this collection’s about, what we’re about up here, because in that incredible song, wrote at the height of his power, you know, you know after we had gotten here, gotten our freedom, and the Industrial Revolution came and World War II, and it was kinda learning how to live in the modern world, if you will, um, and um you know, Springsteen called it, you know, a runaway American dream, you know, in other words, we’re here, we’re running fast, and really at some point not even knowing exactly why we’re running but one thing tonight for sure when we’re in this town, all over America, he talks about, you know, how this town rips the bones off your back, it’s a death trap, it’s a suicide rap, and we gotta get out while our soul’s still young, while our spirit’s still so young, because so many people, um, really, in this country… are hurting and fading away from non-purpose, from mental illnesses, through a lotta things. And I know we have Kicking The Stigma tonight…”

(Kicking The Stigma is a fund Jim Irsay established within the Colts’ organization emphasizing addressing mental health issues openly. Bestowing grants to mental health organizations in Indiana and beyond, while soliciting financial support from the public, its status as a charitable organization and its financial mechanisms are far more opaque than if it were a non-profit.)

“…we’re helping several causes with that but you know again, you know I think as artists, artists look to guard dreams and visions, you know, they look to promote those. And you know, to break this trap, we’re gonna run till we drop and we’ll never look back, and he said, he says, I’m just as scared and a lonely rider…out on that wire… and he talks about I wanna know how it feels, I wanna know if love is wild I wanna know if love is real.”

(He’s winging this stuff free-style, needless to say, cribbing the “Born To Run” quote-bits off a device as he rattles along. Anyone ever called up in front of class for an oral book report about a book they’ve only scanned will recognize the crispy Ritalin rush of reading from the back cover blurbs.)

“And, and, to me, this song is so so powerful when it talks about the soul and the spirit on the reasons we exist, because I talk all the time, being up here, spiritually, and I think to me it’s really important what we do we do together and what we do we have to do with individual courage as well to support each other because it’s all in the end in this room about that feeling of a higher power, of that love of the bigger love and that’s what brings us together and keeps us together and keeps us safe. There’s a lot of insane people on the streets today.”

(The Four Seasons, the five-star hotel where Jim Irsay’s entire entourage is staying, opens out onto Market Street, where a small share of San Francisco’s homeless are staying, out on their own, complete unknowns, no direction home, scrounging their next meal.)

“I look at it as all of our responsibilities, I know these artists, when they go to the stage, they go to entertain, just like when we play football we go to entertain. And um, its, you know, the closing of that song is, um, so powerful, you know, together we can live with the sadness…I love you! with all the madness in my soul. Someday, and I don’t know when we’re going to get to that place where we really want to go and walk in the sun. But until then tramps like us, baby we were born to run. And you know, to me, now, I tear up every time I read that…the power of those words…the soul-felt-ness of those words and, um, we have it out there [gesturing, though not actually in the direction of where The Collection is set up] I know with Kerouac’s writings and so many other writings but what we do tonight…these artists behind me, I mean, they bring it to the stage to try to uplift the world and everyone in this room, just like when when our players bring it to the field because in those moments, it’s so very special.

“And we try to gather all this memorabilia together to honor the history that’s gone on for those before us, and um it’s so important to me to change the world because I…I… I’ve just, you know, it’s driven in all our souls but we can all do more. Get up tomorrow morning and do just a little bit more…because–”

“WOOO-HOOOO!” The sheer dynamic tension has probably blown the mind-gasket of one of the Deadheads magnetically drawn here tonight by Jerry’s miracle guitar.

“Thank you!” Irsay says, not losing a beat, not skipping a step, not dropping a stitch. “Because as JFK did say, it’s not ask what someone can do for you but what can you do for them, you know….so I just wanted to touch on that special lyric, some of the thoughts in my mind….”

Those are just some of the touching thoughts in Jim Irsay’s mind; there’s about half an hour more of press conference to go. The show can wait — must wait. For the next half hour, this is The Jim Irsay Show. His handlers have let it be known, loud and clear, that in the great spirit of generosity permeating this entire beneficent evening, this incredible all-free-ticket event, Jim Irsay — or the Colts, or Kick The Stigma, or somebody — will be making two terribly generous donations of $25,000 each to two very worthy local tax-deductible charitable organizations. [Cue polite but enthusiastic applause.]

The questions raised at the press conference are tough, focused, determined to gather the hard facts of this curious, eccentric exhibition of great wealth and grandeur. Just how much did this whole extravagant soiree cost? Do you have any other reasons for creating this huge, beyond-mega-expensive blow-out, other than sheer personal indulgence? Are you trying to get San Francisco or other cities to build you a museum? How much are tonight’s stars getting paid? How does this work as a tax write-off? And those wonderful charitable donations you’ve just mentioned, that pair of $25,000 checks you wrote — How do they stack up against the costs of throwing this event? What’s the deal here? Oh, and are you really going to try to sing tonight?

Of course they didn’t ask any of that! You didn’t fall for that, did you? What the hell were you thinking? By the warm fluid standards of contemporary journalism, this press conference is only 10 or 20 or 37 degrees more embarrassing than usual, posing non-questions that would humiliate a local tv-news weatherman reporting from the bunny-farm section of the children’s zoo. The assembled press are just so pleased to be in the presence of such greatness, such largesse, such silver-platter hors d’oeuvres service‚ and such a really great collection — so pleased to personally welcome The Jim Irsay Collection and The Jim Irsay Band to Our Fair City, and perhaps even more pleased that Jim Irsay himself has shown up an hour or so late, in order to keep inhaling all those wonderful little canapes, and the free booze so generously offered on the press-privileged side of the velvet ropes. (Oh, and one more question: Are there any more of those little golden empanadas?)

“The evening also will feature a concert by The Jim Irsay Band, a band ‘which has never existed and will never exist again.’” – from the press release for The Jim Irsay Collection

The show is late in starting, half an hour dragging toward 45 minutes late. Bill Graham, always absolutely adamant about all shows starting promptly on time, is no doubt clawing away the dirt over his grave, bent on restoring order in his realm. Since the press conference finally swirled away, Jim Irwin has been hosting an informal 12-Step get-together in his dressing room, until at last one of the Colts’ front office suits firmly gets rid of the visitors, bringing in Tom Bukovac with an acoustic guitar. Jim Irsay wants to go over “Born To Run” just a few more times before the show can start. He’s decided he’s going to open the night singing “Born To Run.”

Earlier, before the press conference, I’d dragged Bukovac out of catering to ask, to find out…well, you know, basically: What the fuck? I mean, obviously Jim Irsay’s singing sounds like the wrong end of a cat fight, right? Only less rhythmic? Help me, please, make some kind of sense out of this situation, just in case there’s any sense to be made. Mike Mills was finishing up his salad as we spoke (you know him; he’s the guy who told Spotify’s CEO, the one complaining that musicians weren’t cranking out tunes fast enough to earn a living, to “Go fuck yourself.”) I was counting on Bukovac’s reality meter, like having a trusted stage-tuner amidst your stomp-boxes.

On the Ray Wylie Hubbard scale, Bukovac easily ranks as cooler ‘n hell. At 13 he was playing in bands in his mother’s bar, the Surfside Lounge, on the beach between Cleveland and Akron. He’s conquered Nashville’s hard-won studio world, playing on more than 700 big-time albums, and touring with Vince Gill, Joe Walsh, and the rather particular John Fogerty. As Covid hit, Bukovac started up a YouTube channel, “Homeskoolin,” from his garage studio and it blew up big because he opens up easily about his vast playing experience, shooting the shit while remaining a resolutely unshaven non-beer-snob guitar-jock hotshot. Oh, and he avidly collects both workhorse guitars and rare football cards. Among all the folk I’d spoken with —everybody in shouting distance, one and all, was on the Jim Irsay payroll — I was counting on Bukovac to cut through the crap. That was his day-job definition in the studio, and it was why “Homeskoolin” had gone large.

Except now, clock ticking louder by the minute, audience waiting, show still holding, here was Bukovac in Jim Irsay’s dressing-room, ever so gently playing through the chords to “Born To Run.” Of which there are like, swear to God, no less than 20 — including all kinds of F-sharp suspended 4ths, and B7 4th suspensions, and a couple of busy modulations into different keys, all from back in Springsteen’s young ultra-ambitious operatic era. On the other hand, as sports-writer Dave McKenna wrote, marveling over a YouTubed desecration-derby of “Blowin’ In The Wind,” Jim Irsay’s specialty is the Key of Off.

At the back of the room, Jim Irsay’s chief of security is like a silent hawk, but everybody else — Colts’ suits, and Jim’s lovely girlfriend, Michelle, and his personal assistant, and her assistant, and production crew— is scuttling to set him up with the lyrics to “Born To Run,” the song he intends to open the show. Bukovac’s main focus, the final high hurdle before the show can finally start, is the outro section, with all those dramatic operetta-esque “Woah-ohh-ohh-oh…” parts flung skyward high and hard. The symphonic string section has worked up a gorgeous little part that fits perfectly; they’re already onstage, waiting and wondering. Everybody’s wondering, other than Jim Irsay.

One thing you can say for Jim Irsay’s singing, even back here in the dressing room: it’s loud. Thanks to Bukovic’s slow, calm chording, reading along through the runaway American dream, the suicide machines, the mansions of glory, and the tramps like us, Jim Irsay’s able to keep it down to a sludgy rumble, but those woah-oh-oh-ohs…they’re just too tempting! How can he possibly keep from hollering at ‘em? Springsteen did, so why can’t he?

The very soul of kindness and good sense, Bukovac suggests Jim Irsay maybe try pulling back a bit on his WOAH-OH-OH-OHs, maybe make them mere woah-ohs-oh-ohs. Bukovac is sketching out an eloquent acoustic armature, slow and minimal, but rich and melancholy. It’s the way real musicians play, spare and open, implying everything and leaving huge space for others. He counts out the repeats, so Jim Irsay can keep track, if he’ll just listen. Jim Irsay keeps insisting that the song makes him think of Jim Corce’s “Operator,” which is a pretty unique interpretation, and a complete non sequitur, but one that might suggest a quiet, wistful delivery. No dice —every single time there’s a death trap or a suicide rap or a town ripping the bones from your back or something equally dramatic, Jim Irsay cranks up, hard and loud, because that stuff needs to be emphasized loud and hard and ultra-dramatic. And look out! Here come those WOAH-OH-OHs!

Somebody wise has gone to fetch Carmela Ramsey, who played both offense and defense all through rehearsal. She plays fiddle and mandolin, she plays violin when the special teams symphony string section gets put into the game, and she sang gorgeous harmonies throughout. To her credit, bless her heart, she didn’t know the “Born To Run” woah-oh-oh-oh schtick during last night’s rehearsal — she grew up in bluegrass — but she came prepared and precise tonight, and if Jim Irsay would just listen, could just listen, would try to listen to Bukovac’s good and helpful counsel, offered again and over again, to maybe cool down the wounded mammal WOAH-Oh-OHs, Carmela is equipped with that super-musical sense, with years of Nashville studio backing vocals under her belt, that could somewhat sweeten the sour, or at least spray-paint over it. “You could maybe just sort of purse your lips,” she offers helpfully, trying to get Bukovac’s gentle advice to penetrate, to sink in, or simply be heard.

“Irsay’s passion project is an unusually personal form of philanthropy and even therapy.”

– New York Times, December 9, 2022

I have some experience with budgeting the logistics and costs of moving musicians, crew, equipment and entourage from point to point, airport to airport to hotel to venue and back again, rehearsals, restaurants, soundchecks, per diem payments, from load-in to load-out and on down the road — although never with the luxury of six private planes (four of them belonging to Jim Irsay himself) to make things ever so much easier.

Here’s what this particular entourage looked like, roughly: A full contingent of Indianapolis Colts’ cheerleaders flown in, along with four backup singers, and twin guitar collection techs (actual twins, actually), and a university librarian/literary tech-specialist who looks after the Kerouac scroll and the Alcoholics Anonymous Big Book galley-proof. (And maybe the Austin Powers glasses, I don’t know.) There’s a small but efficient suit-and-tie cadre from the Colts’ front office, plus Jim’s wary-eyed full-time security chief and his support, and Jim’s personal assistant, and her assistant. There were three lovely models on hand, for reasons unknown, but dressed in formal evening gowns. There was at minimum a trio of publicists, none wearing evening gowns or cheerleader uniforms. There’s the house sound engineers and stage monitor crew and stage and house lighting techs (along with local crew) and the guy running the huge customized The Jim Irsay Collection logo displays and the teleprompter, song by song, line by line. Jim Irsay has commissioned a documentary about himself, so there’s a camera/sound/lights crew documenting Jim Irsay’s every breathing move, his every moving breath. There’s a still photographer too, who usually covers the Colts, but comes along for each of the band’s roadshows. There’s a small gaggle of Jim Irsay’s friends and admirers, flown in from out of town to enjoy another great party. There are several artist managers, tour managers, and sundry booking agents on hand, just to add color and contrast to the cheerleaders.

The lowliest single rooms available at the five-star Four Seasons Market Street where the Jim Irsay entourage is staying run $650 per night (the hotel mainly has more elaborate suites) at a group discount for over 10 rooms. Under these circumstances, including musicians, singers, some spouses, managers, and assistants, guitar techs, crew, publicists, pilots, front-office staff and cheerleaders, 40 to 50 rooms would be required — say $26,000 to $32,500 a night, barest minimum, before taxes, not including incidental fees like room service and mini-bar — you know how musicians and cheerleaders are. The late night after-party in the hotel restaurant, with open bar, elegant entrees served by a cohort of attentive after-midnight wait-staff, may have been a little pricey, but with luck, hotel costs might possibly total less than a hundred grand. Jim Irsay is a notoriously generous tipper, in cash.

Jim Irsay’s promotional publicity emphasizes that he played football at Southern Methodist University, and typically attributes his use and/or abuse of pain-killers and opiates to the injuries he sustained there, though sometimes it’s as a result of weight-lifting with the Colts. In fact, he hadn’t played football since he was a freshman in high school, but on a whim decided to walk-on at SMU. That’s the kind of whim sportswriters call “foolhardy” and regular folk call “batshit crazy.” Jim Irsay calls it “a George Plimpton experience,” after the upper-crust trust-fund writer who worked out with the Detroit Lions, went into a late summer inter-squad scrimmage as quarterback, bumble-fucked miserably through a five-play sequence, and got a best-selling book and a highly celebrated writing career out of the process, vigorously repeated for hockey, golf, boxing, baseball, and tournament bridge.

This entire Jim Irsay Band Experience, both Band and traveling roadshow Collection, does seems like a George Plimpton experience, but stretched out to astonishingly absurd lengths at maniacal cost, promoted, publicized, advertised, and funded far beyond a fumbling five-play fuck-up. As Plimpton’s fantasy sprang to life from a sense of privilege, of noblesse oblige — with constant aw-shucks statements of humility to make it palatable — Jim Irsay appears to have convinced himself not that he’s having a Geoge Plimpton experience once again, but that he is George Plimpton. And that George Plimpton must undoubtedly have been a bad-ass rock’n’roll singer too.

Speaking of noblesse oblige, I’ve personally been feeling a powerful itch, an irresistible, overwhelming urge: It’s true that I can barely throw a wobbly spiral 20 yards, but what does that matter? Why don’t I step in and play quarterback for the Indianapolis Colts? And I want to call the plays, all of them, according to my whims. But the thing is, I don’t want to get hit. I want to be quarterback, see, but I don’t want to have to suffer — I just want to step in and do it, safely, no risk. Oh, and I don’t want to have to learn any plays or signals or anything. I want to read ‘em off a teleprompter. So what do you think, Jim? Sound like a plan?

It’s a fine time to be a billionaire. Silicon Valley or Saudi Arabia, Russia or Florida — all the best people are either billionaires, or pretending to be. Yet billionaires have troubles too — the margins on money-laundering these days are outrageous, and in the post-WikiLeaks era, offshore banking seems so porous and precarious, so very less than Swiss. It’s not that it’s lonely at the top — it’s the opposite. A billionaire can buy friends by the bushel, by the barrel, or by the band-load. No, the real problem is it’s just too damn crowded at the top. What’s a poor billionaire to buy that will show the world just how special a billionaire he truly is?

In interviews, Jim Irsay scoffs at the notion of spending his scratch on yachts, and even for a guy with four personal private jets, he’s got a point: Those tacky Russian oligarchs have made mega-yachting look like a weekend weenie roast at the trailer park. Meanwhile, the price-tags on fine art makes guitar collecting seem as if you’re hoarding empty milk cartons. All the Van Goghs have been snatched up, while Picasso over-produced, so the high roller hot-dice action has a DeKooning pulling down $300 million and Jackson Pollock’s “17A” (basically, a much better value, yard-for-canvas-yard) at $200 million. Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” where the guy looks like he’s hearing Jim Irsay sing, went for a low, low bargain price of $119.9 million; the last Rembrandt under the hammer went for $180 million. They’d surely let the guitar collector crowd into the auction house, but mainly just to watch from the cheap seats to see how the big kids do it.

“Yet rather than accumulating expensive toys in some crass display of wealth, talking with Irsay reveals that he has a deep love and appreciation, not only for the timeless music these instruments were used to create but also what they represent as cultural – and indeed countercultural – objects.

– Guitar.com December 31, 2021

Timeless. For just a smidge under $1 million, Jim Irsay scooped up the Fender Stratocaster that Bob Dylan played for three songs at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, then abandoned, first for an acoustic encore, then left behind forever, forgotten in the plane that flew him away, never to be touched again. You’d be hard pressed to scrape any authentic Dylan DNA off the guitar at this stage, in case you were inclined to create authentic Ray-Ban-wearing electric-era Dylan clones. Only three songs, but three songs that loom large in historical mythos, every detail still argued and fussed over.. So maybe a million bucks was a mighty bargain. Then again, in 2021, Dylan sold his entire song publishing catalog, his entire body of songs for $200 million — the price of a single Jackson Pollock painting. They’ll make somebody a whole lot of money — the month after Dylan’s demise, they might recoup the entire cost. But aside from the money-spinning potential, which of these two purchases is less “a crass display of wealth”? Which one of these suggests genuine appreciation for “timeless music”? Oh, and with a singer as rhythmically-challenged as Jim Irsay, what does “timeless” truly mean?

The show starts at last with one of those booming announcer-voiced video montage effects they use for pro wrestling and monster trucks — “Get ready, San Francisco!” roars a voice twice as masculine as God — and now The Jim Irsay Band occurs. “Born To Run” is mercifully brief, but the string section fits impeccably. On “Lawyers, Guns, And Money,” it turns out Mike Mills can do a near-perfect Warren Zevon imitation, while Jim Irsay sounds exactly like Jim Irsay on his verses, taking immense child-like delight in hollering “Shit!” and “Fuck!” Ann Wilson kills, crushes, slays, and does it standing up this time. Stephen Stills digs in, but discovers somebody must’ve messed up the settings on that goddamn glorious tweed Bandmaster of his. Instead of taking the solo, he gives harmonica player Billy Branch the high sign, and Branch puts a fresh coat of a blue paint on “For What It’s Worth.” Branch is there again when Buddy Guy hits the stage — they flew out together, sharing stories of old South Side Chicago days that had their whole section of the plane leaning forward to listen. Buddy Guy is maybe just a year or two too old to need to rehearse to play blues. He didn’t get lessons from Jimi Hendrix; Jimi Hendrix used to lug his tape recorder out to go get Buddy Guy lessons. At 86, he hasn’t lost a step; his playing, always bold and brash, is as cocky as ever.

Jim Irsay’s featured vocal numbers are things like “Hurt,” the lambent Trent Reznor lament that for a certain generation is Johnny Cash’s greatest hit, or a big production number of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb.” Both have a drug-factor to them, and both dovetail with Jim Irsay’s extended drug-abuse introductions for other songs, like the one about how Kurt Cobain quoted Neil Young’s “Hey, Hey, My, My” in his suicide note, only with a few extra-dramatic truth-stretching embellishments and fantasy additions to the known facts. Building the show’s set list at rehearsal, Bukovac and the band had worried about how to follow John Fogerty, but Jim Irsay was solid brass bravado. “I’d follow anybody in the world with our version of ‘Comfortably Numb.”

More experienced heads have prevailed, and now the Pink Floyd show-stopper comes right before Fogerty. It arrives equipped with green Floyd-a-rama laser-lighting video and a customized mind-boggling Jim Irsay-a-rama introduction, more like W.C. Fields than ever in its surrealist three-card shuffle of history’s deck. “You know, I wanna tell you a little story. When Thomas Edison discovered light,” he explains to the audience, “George Westinghouse was with him.” Edison and Westinghouse were, of course, bitter corporate arch-rivals, while light had actually been discovered a week or so previously. “Edison was the brilliance of brilliance, was the first to get that light on, and George Westinghouse asked him, he said, ‘Thomas, what was it like, you know, when you first pulled that switch and light came on?’ Well, as you can imagine — or maybe just go ahead and make it up for yourself; what the hell — it was pretty darn amazing. Thomas Edison told George Westinghouse it was like God was there himself, and so that’s where we get the phrase “lightning in a bottle.” You learn something new every day, and sometimes even more frequently. Anyway, the point was that Jim Irsay wanted us to know that he and his band had captured lightning in a bottle with “Comfortably Numb.” “You might want to get your phones out for this one.” Cue the green laser video.

Those concerns about following Fogerty, unlike Jim Irsay’s historical tales, were reality-based. John Fogerty comes bounding off the stage energized after his bulletproof six-song set, sweating in his blue plaid cowboy shirt; a guitar tech lifts his black Les Paul off and takes it away. He’s just whipped out a nickel-plated little string of Creedence songs that can’t help feeling more like American culture than classic rock, songs he carved with his own hands, singing them in that voice of his, that unmistakable, unfathomable voice, a voice that always leaves a hollow empty spot when every Dad Band in the world tries to cover “Proud Mary” or “Fortunate Son.” That unmistakable voice, those hand-carved songs, all the meaning, all the buried feelings they stir up and set loose, and all the whole audience dancing.

As Fogerty stride-sprints off across the side-stage, one of the Colts’ front office suits cuts him off. “Hey, John! Jim Irsay, the guy who put this whole thing on… he’d like to say hello and meet you before you go…”

“Sure!” says Fogerty, pumped full of stage energy, pulling up short just before the stairs. “Where is he?”

It’s not fated to happen, their handshake, their quick little meet-and-greet. Jim Irsay’s back out onstage, microphone in hand. “John Fogerty!” he’s yelling. “I mean, I ain’t no fortunate son! I mean, I got no silver spoon! But when the taxman does come to the door, I make it look like a rummage sale! I try to avoid the tax man!” And then he gets up in front of that bad-ass, kick-ass, monster-ass band, closing the show as they roar into “Gimme Shelter,” while Jim Irsay reads the lyrics off a teleprompter, standing up, front and center. It wouldn’t be right, it wouldn’t be true, it would be wrong to say that he was singing. A singer just left the stage, and has to get out of here and go home.

“But I don’t possess it. I don’t have any ownership over it. I want to make that very fucking clear. With the museum it’s about, ‘How do you create the Willy Wonka factory? How do you sell the golden tickets?’”

Jim Irsay, speaking to Guitar.com on his dream of a museum built for his collection

I’m maybe a little slow getting to the after-party at the Four Seasons, but not to worry; a publicist is calling to shepherd me along, to make certain I’m coming, because Jim Irsay is waiting, center table of the gracious restaurant, closed to the public. The show ran late, of course, with the attendant Civic Center over-time costs. It’s long past midnight, and cold outside the hotel, but maybe those living on the street, no secrets to conceal, have gotten used to it. Up on the fifth floor, the restaurant boasts 180-degree views of what’s left of San Francisco’s skyline, but you can’t see the sidewalk below.

Hustled to a seat next to Jim Irsay, and then the dam bursts, splits wide open, floating free-associated litanies of sainted celebrities, scrawling sketches of near-connected statements and half-thoughts, an elaborate word-salad tossed right there table-side, name after famous name after fetishized name: John Lennon, John Mellencamp, John Fogerty, Johnny Cash, Johnny Depp, Elton John, and, uh, you know, Bruce Springsteen and Jerry Garcia and Hunter S. Thompson — an old, old friend; did you know The Collection includes the original “Red Shark” Chevy convertible? From “Fear And Loathing”? — and Kris Kristofferson and Kurt Cobain and Janis Joplin and Tom Petty — wasn’t that sad? — and Neil Young and Charles Manson — struggle with the ethics of buying artifacts, but he’s part of history — and Bob Dylan and Keith Richards and Art Garfunkel and the Who and John Belushi and Cathy Smith and Cameron Crowe and Willie Nelson and Jason Isbell and Peter Berg and…Hey! Hold on! Wasn’t the Red Shark a rental? Didn’t Thompson desecrate and disembowel and destroy it, ditch it, and replace it with a fresh rented white Cadillac? How could it possibly be the original one? Unless maybe Edison and Westinghouse got together to restore it.

“Rambling” might be one way to describe this deluge, but so would “manic ceaselessly self-obsessive chattering clattering nattering non-stop name-dropping monologue.” Over the course of about an hour and a half, I wedged in maybe five questions, and had to work those in with a hammer and chisel. In fairness, Jim Irsay would actually slow down and pause and tone it down, downshift into second-gear and sort of listen and then use your question as a brand new launch pad for what was on his mind and needed to be spilled forth, and then followed with something that might connect if you added something else or else something other than that. With your question lost in a cloud of dust in the rear view mirror.

Once, many years back, when Steve Earle was freshly sober and drinking pitcher after pitcher of Pepsi, I sat on a tour bus — ours, not his — and listened wide-eyed to a manic monologist in Jim Irsay’s league, and once in Xalapa, Mexico, there was a loosely-wired gringo named Snake who was working his way up into the monologuing major league too, but Snake was most likely on some kind of rocket-powered non-Pepsi chemical assistance, so I don’t know if he counts. Besides, Snake wasn’t famous, so who cares, right?

If I hadn’t already heard so many 12-Step statements of sobriety from Jim Irsay at the press conference and backstage and onstage, lecturing the crowd between songs about the perils of drugs other than molly — molly was okay tonight, he said, just before having autographed footballs flung out into the crowd — well, I’d just naturally have assumed that Jim Irsay was every bit as rocket-powered as Snake. I don’t know — maybe he was drinking the same kind of full-on fuel-injected Pepsi as Steve Earle. His lovely girlfriend Michelle, very attentively kept him topped off and even freshened his ice, which was ever so thoughtful of her.

Anyway, all his collecting for The Collection started with Elvis — so many things do — back in Jim’s more indulgent days, his official non-sober era, during which he likes to say he spilled more drinks that most people swallow. He had a running buddy, you know, who seemed to owe him a bunch of money for something not worth mentioning. And the buddy’s parents owned an Elvis museum. You know how that goes. Anyway, the buddy wanted Jim to have Elvis’s guitar, and Jim didn’t really want it — maybe he kind of wanted the money, I guess — but the guy insisted, and you know how it goes: You end up owning Elvis’ Martin D-18. And then Kerouac’s typewriter scroll, and a bunch of other stuff. Jim Irsay keeps saying he’s really a curator, not a collector, a steward of history. A history constructed of valuable items, of guitars and Willy Wonka’s Golden Tickets.

There was more, lots and lots and lots more —so much more. The best cost estimate I’d been hearing for bringing this whole traveling circus and the great Jim Irsay Collection sideshow to San Francisco was, according to several nervous employees, around $3 million. Jim Irsay tells me it’s more like $10 million. You could probably buy two or three pretty good guitars for that — Willie Nelson’s “Trigger” and Bruce Springsteen’s Fender Broadcaster are sitting out there going to waste right now — but what the hell; it’s Jim Irsay’s money to incinerate. I’m pretty sure both of the tax-deductible charity donations of $25,000 were included in the grand total, but since that’s hardly even one night’s hotel room cost, it’s hardly worth mentioning, other than at the press conference or onstage, in front of the appreciative free-ticket audience.

Jim Irsay has this thing he tells his interviewers about how he can dead accurately predict the price of a guitar he’s planning to bid on. So he talked about that for a while, and I guess it sort of makes sense, at least in the sense that after you’ve spent like $3.9 million for a guitar, you can say: “I knew it!” I couldn’t help feeling that it would be more impressive if you did your prognostication out front of the auction, in advance, in public, but that’s not really the Jim Irsay method.

Water-skiing behind Jim Irsay as he swerved back and forth was starting to make my arms tired. Even when I sort of rudely crashed his one-man-party with a question, there wasn’t much hope of getting a direct sensible answer to anything sensible and direct — might just as well check out his guitar market predictions. He’d just scored big buying John McVie’s bass at such a pawnshop price, so I wondered what he thought James Jamerson’s bass might go for?

I drew a blank — or a Jim Irsay speed-talking version of a blank. It didn’t register. It didn’t seem like he knew what I was talking about, which was strange for a guy with his ultra-accurate understandings. James Jamerson, as any bass player anywhere in all the world will tell you at fabulous length, was the Motown bass player who blew everybody’s mind back then and blows everybody’s mind today. Jamerson was the guy who played the torturous, tantalizing bass part on Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” while so dead-drunk he had to lay on the studio floor when he did it. They auctioned off a bass that once belonged to Jamerson, I guess, but it wasn’t the Fender P-bass he called the Funk Machine, the one he carved the letters F-U-N-K into, the one with its neck so fucked-up nobody could play it but Jamerson, and he made it sound the way every bass player worth a damn has been copying ever since — made it sound like James Jamerson. Someone stole that bass before he died, and it’s never been seen again.

How much, Jim Irsay, would you predict that one’s worth?

Jim Irsay doesn’t appear to know that one. He’s not terribly interested. He trotted off into a comparatively brief explanation about how it wouldn’t be worth much, not worth the truly big bucks, because James Jamerson wasn’t famous. For something to be really worth the kind of money Jim Irsay was willing to shell out, you see, it has to belong to somebody famous. A celebrity. That makes all the difference.

He wasn’t much interested, and he had other stuff to say about how he had bought other stuff. Did you know he owns Willy Wonka’s Golden Tickets? Yes, indeed, he does! He really wants you to know that, because it’s so very (!Cuidado! Here comes that way-over-used i-word!) so very iconic. It kind of tells his own iconic tale, the way he tells it. It’s a symbol, see? Of how he got the keys to the kingdom, the chocolate factory and the golden ticket and the whole iconic schmear… but he also wants to assure you that just because you’ve got the Golden Ticket, it doesn’t mean you don’t suffer, too. Everybody knows you have to suffer to sing the blues. Unless you’re making others suffer by singing them.

Okay, so Willy Wonka — swell, but how about Sister Rosetta Tharpe? Sister Rosetta had a bunch of completely cool guitars through the decades of her career, and she was one of the very earliest electric guitar players ever. Plus, she was really, really famous — she got married at the Washington Senators’ ballpark, drawing 25,000 paying customers — paying customers. Beyond that, if anybody can be said to truly be the Father of Rock’n’Roll, it’s Sister Rosetta Tharpe. How about that cool Gibson SG Custom she played in the 1960s, the one with three pickups and gold hardware and the devil-horn cutaways — how much would that be worth?

I was totally losing Jim Irsay. He didn’t know, didn’t care, and it didn’t have anything to do with him. Couldn’t tell if he’d ever heard of Sister Rosetta, but as the curator of history goes, she wasn’t Classic Rock, that’s for dead certain. There’s famous, and then there’s famous enough to have those Morning Zoo radio dudes cue up another commercial-free DoubleShot RockBlock. By that standard, Sister Rosetta Tharpe isn’t only Not Famous, she never existed.

It was late but it felt a lot later. Jim Irsay kept talking, talking, talking about just how incredible the museum would need to be to properly display The Jim Irsay Collection, and how he wasn’t really a collector at all, but a curator, a curator of history, a steward, simply a caretaker of important historic artifacts, and how maybe the next stops on The Jim Irsay Band’s World Tour would be Paris and Hamburg and Maui. There were famous names thrown in and around too, but I found myself thinking about Tom Bukovac, a super down-to-earth guy who’d never aimed at fame, who’d only ever aspired to being a team-player, a session cat, the kind of guy who knew when to fill in the spaces and when to leave space for someone else. I’d dragged him out of catering, knowing he was a straight-talker.

He was, and in talking straight, he told me he really genuinely liked Jim Irsay. Genuinely. He calls him Jimmy. “This thing started in Nashville, at one of his guitar exhibits, before the band started happening. I came out to a hotel, he was doing the exhibit there, first time I met Jimmy. There were all these instruments around but we weren’t planning on playing or anything. At the end of the night, I said, we should play a couple of tunes, play a couple guitars, couple of amps. There was no drummer, no bass player. Next time we did it was in a hotel ballroom…” and The Jim Irsay Band thing mushroomed from there.

Bukovac told me about a friend, a guy he knows from that famous and famously expensive vintage guitar store in Nashville who had been struck down with a bad disease, and when Jim Irsay — when Jimmy heard about it, he immediately wrote a $25,000 check. Then, later on — and Bukovic emphasized that nobody came asking — he wrote another check, this one for $250,000. “I love Jimmy! He’s been an ace! It kills me when I hear people talk shit about him. I think people are just inclined to hate rich people.

“He reminds me so much of all the people that used to hang out at my mother’s bar up in Cleveland when I was a kid. Fans of music, man — just loved music, man! Jimmy loves music more than anybody I know. He gets moved by a song way deeper than I do. He’s just like overwhelmed by songs. I think that’s beautiful. I wish that I could get back some of that innocence, you know? And it’s infectious. And he likes to throw parties where he gets to meet some of those people. Maybe he’s gotta pay a few dollars to do it, but he’s got a few dollars. Why not?”

I couldn’t help thinking about George Plimpton, partly because Jim Irsay name-dropped him, too, but partly because of how Plimpton ends his tale of trying to impersonate an NFL quarterback. One of the real-live Detroit Lions, Harley Sewell, a veteran offensive lineman, is trying to cheer George up, telling him kindly that he did just fine. Plimpton, full of rue and remorse, runs down all the screw-ups he managed to squeeze into his brief moment in the big leagues: he lost 20 yards, he fell on his ass, he had the ball ripped away from him, and his only pass attempt was ludicrous. “You didn’t do too bad… considering,” Harley told him.

“’Harley,” Plimpton said ‘’You’re a poor judge of disasters.’”

Bukovac’s attitude was a fine one, a great way to enjoy the hell out of one of the oddest, best-paying gigs ever. Maybe he has a Harley Sewell football card in his collection. I could see his points, but I couldn’t not hear Jim Irsay — not just his ceaseless scattered stream of chatter and famous names and nonsense, but the way he sounded when he had a microphone and audience in front of him.

I tried once more, offering Jim Irsay my really brilliant idea — okay, maybe not pure genius, but close enough — about me stepping as quarterback for the Colts, with no actual applicable skills, and nobody tackling me, while calling all my own plays, with me reading those plays off a teleprompter — you know, the George Plimpton experience. Only a lot more chickenshit.

I was losing him. I think it was starting to dawn on him that I was an idiot. I pushed it a bit, trying to see if he saw any comparison, any at all, but he couldn’t. He really genuinely couldn’t understand what I was talking about — it seemed absurd to him. “I mean, those are professional athletes,” Jim Irsay told me, late at night in a lovely private restaurant full of the best musicians money could buy.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

The post A Fine Time To Be A Billionaire appeared first on SPIN.